Science and the Nation (Winter 2025)

Section outline

-

-

Instructor: Karl Hall

Number of credits: 2

Course level: MA

Time: Thursdays at 13:30

Location: QS A103

Instructor's office hours: Mondays 14:00-15:00, Wednesdays 11:00-12:00, Thursdays 15:30-16:30; and by appointment

Zoom option: If you require Zoom access for health reasons, use this link. Please alert the instructor beforehand if you will not attend in person; online access is not automatic.

Prerequisites: None: no background in history of science is required.

Course aims:In 1815 a dozen Swiss naturalists and physicians gathered outside Geneva to form a federation-wide learned society devoted exclusively to the natural sciences, “drawing together the ever more diverse parts of our body politic.” The founders of the Société Helvétique des Sciences naturelles cast it as based on a liberal politics without regard to social station, while also cultivating membership across different levels of scholarly dedication and achievement. Vowing not to seek out despotic patrons, and “inspired only for fatherland and science,” they planned to meet in a different canton every year with support from town fathers. Separated by laws, customs, mores, and language itself, naturalists from the twenty-two Swiss states convened in person “in order to overcome the prejudices that these differences might nourish, to the great detriment of the harmony which is so necessary to us.” In the 1820s German-speaking naturalists and physicians began congregating annually at rotating meetings in Saxony, Hesse, Bavaria, and eventually Prussia, with Berlin hosting the largest gathering to date in 1828. Alexander von Humboldt, the organizer of the Berlin congress, called it "a noble manifestation of scientific union in Germany; it presents the spectacle of a nation divided in politics and religion, revealing its nationality in the realm of intellectual progress." Many bilingual scholars attended the annual German-speaking gatherings (including Vienna in 1832, Breslau/Wrocław in 1833, Prague in 1837, and Graz in 1843), and the congresses were soon emulated by Britain, France, Italy, the Scandinavians, Hungary, and eventually Russia, partitioned Poland, and the Czechs. At a time when most university appointments were closely controlled in Vienna, Berlin, and St. Petersburg (albeit with important variations in administrative oversight and corporate identity), these congresses offered a seminal early mechanism by which scientists could identify themselves with national communities. In the early stages, at least, the idea of the nation could help transform the local preoccupations of a seemingly fragmented Republic of Letters into something more universal. Where British and especially French scientists often fell back on an auto-universalizing patriotism in support of their endeavors, scientists east of the Rhine had no such luxury, and numbered both some of the most ardent advocates of a renewed Republic of Sciences as well as fierce proponents of national imperatives for scientific research.

Our task in this course will be to investigate the various ways in which natural scientists reconciled the universal claims they associated with specific forms of knowledge about nature and the national aspirations which so many of them also entertained during the long nineteenth century. Themes familiar from the canons of nationalism—comradeship with people one has never met, collective memory (in the form of textbooks), a growing capacity to imagine a collective future—all figure with scientists as well. Yet our aim is not simply to add case studies of scientists to methodologically familiar intellectual drivers of nationalism from literature, philology, history, philosophy, sociology, or the fine arts. The development of rational forms of administration that were often crucial to understanding how nationhood was constructed must sometimes be investigated in close relation to science in particular. Both forms of patronage and rewards for achievement (discoveries and inventions) that might seem peculiar to universal science can be more clearly explicated within processes of national formation. The very notion of "scientific community" as a historical social formation indeed owes much to nation-building tropes, notwithstanding its cosmopolitan claims.

It is understood that few students will have specific research interests in the natural sciences (Naturwissenschaften, természettudományok, естествознание, přírodní vědy, nauki przyrodnicze, природознавство, 自然科学), but the course further provides the opportunity to interrogate the normative status of other forms of scholarship (Wissenschaft, tudomány, věda, nauka) in their relation to the nation during the period when Anglophone "science" ceased to be equated unproblematically with Wissenschaft, etc. Where Polish linguist Jan Kochanowski once insisted (refracting Leibniz) that the "essential polyphony" of universal knowledge could only be enriched via the nationality of science (scholarship), those studying the history of the human and social sciences will find this a useful venue in which to investigate that polyphony through a closer understanding of the contributions—empirical, institutional, and epistemological—of the natural sciences to the languages of collective belonging. By the same token, we will be attentive to the many ways that "national science" could serve as a projection of local and regional agendas—not always merely political, but sometimes constitutive of new and durable forms of knowledge production. Finally, in keeping with recent work on imperial contexts, we will take heed of supranational motives for national ambitions in the sciences. Though the nationality of science is ultimately an incoherent concept, it has nonetheless been important and performative for a variety of Central and East European scientists (and others) determined to participate in the interminable regional debates about the course of cultural, social, and economic development.

Note on primary sources: Each session has a default primary source in English available to everyone. Where sources permit in a given session, the course includes supplementary Central and East European views of the topics under discussion, and these Czech, Hungarian, Polish, etc., options may be substituted as desired. For Iberian, Italian, Turkish, and East Asian sources beyond the instructor's expertise, much will depend on participating student interest.

Learning outcomes: Students will learn to situate the universal claims of the sciences in their historical contexts, while identifying points of continuity between familiar and unfamiliar national traditions of scholarship throughout Central and Eastern Europe. (In less structured ways, interested students also have the option of including sessions devoted to Iberian, Italian, or East Asian science.) By engaging the frequently stronger claims of the natural sciences, they will arrive at a more rigorous understanding of the universalist claims of other forms of scholarship in nation-building contexts. The linguistic aspects of the development of demotic languages of science will be highlighted in comparative terms. In a very limited way this course also doubles as an introduction to the historical sociology of knowledge.Assessment: One presentation in class: 25%; session discussion leader: 15%; review essay: 50%; general class participation: 10%.

Review essay: 8-9 double-spaced pages (12-point font, no fiddling with the default margins; Chicago Manual of Style, full notes). Topics chosen in consultation with the instructor.

Deadline: April 4

With an appropriate essay topic this course counts toward the Advanced Certificate in Political Thought. -

In the eighteenth century academies and learned societies dominated the natural sciences in Europe, from the proliferating academies of the Italian peninsula, to the dominant Royal Society of London and Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris, to their epigones in Berlin, St. Petersburg, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Haarlem, and Lisbon (the last founded in 1779). It was often a point of pride that they enrolled foreign correspondents and maintained formal relations with them even in time of war. Cosmopolitanism was not simply the luxury of nascent professional scientists secure in their sources of patronage, but rather more the necessity of marginal elites whose best strategy for advancing science in their native locales lay in developing ties with colleagues abroad. For much of the eighteenth century the scholarly solidarity of the Republic of Letters was subject to repeated critiques, however, and not only due to the selective rejection of Latin. Once it came to be seen as a "tribe of compilers" (in Fichte's words), the Republic of Letters became subject to new divisions and new solidarities, both disciplinary and patriotic.

We have a surfeit of materials here, so I've recorded a short lecture which we can use as a starting point for the class discussion.

Assigned reading:

Friedrich W. von Ziemietzki, excerpts from Das akademische Leben im Geiste der Wissenschaft [The Academic Life in the Spirit of Scholarship] (1812). (Original German text.)Lorraine Daston, “The Ideal and Reality of the Republic of Letters in the Enlightenment,” Science in Context 4 (1991): 367–86.French option: Jean d'Alembert, "Réflexions sur l'état présent de la République des Lettres pour l'article Gens de Lettres," Oeuvres et correspondances inédites, ed. Charles Henry (1887 [1760]), 67-79.Bohemian option: Ignaz von Born, "Vorrede des Herausgebers an den Leser," Abhandlungen einer Privatgesellschaft in Böhmen, zur Aufnahme der Mathematik, der vaterländischen Geschichte, und der Naturgeschichte 1 (Prague, 1775): 2-4.Prussian option: Johann Christian Friedrich Harless, Der Republicanismus in der Naturwissenschaft und Medicin auf der Basis und unter der Aegide der Eclecticismus (1819). (A review) (NB: This is the same figure who wrote about the merits of women in natural science in 1830.)Hungarian option: Szily Kálmán, “Magyar természettudósok száz évvel ezelőtt,” Természettudományi Közlöny 20, no. 225 (1888): 169–78.Polish option: Stanisław Bonifacy Jundziłł, "Cudzoziemcy w Uniwersytecie," in Ludwik Janowski, "O pismach historyczno-literackich Jundziłła," Rocznik Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Nauk w Wilnie 3 (1909 [1829]), 19-52.Russian option: Nikolai Fuss, "[speech to the Free Economic Society]," Труды императорского ВЭО 59 (1807): 283-293. [It's not a great selection, but see esp. sect. 3.]Suggested reading:

Kasper Risbjerg Eskildsen, “How Germany Left the Republic of Letters,” Journal of the History of Ideas 65 (2004): 421–32.Robert Mayhew, “Mapping Science’s Imagined Community: Geography as a Republic of Letters, 1600-1800,” The British Journal for the History of Science 38, no. 1 (2005): 73–92.Gábor Almási and Lav Šubarić, eds., Latin at the Crossroads of Identity: The Evolution of Linguistic Nationalism in the Kingdom of Hungary (2015).Karol Mecherzyński, Historya języka łacińskiego w Polsce (1833).Döbrentei Gábor, “Magyar tudós társaság történetei, a nyelv országos régibb állapotjának rövid előadásával,” in A Magyar Tudós Társaság Évkönyvei 1 (1833):1–126.Arne Hessenbruch, “Bottlenecks: 18th Century Science and the Nation State,” In The Spread of the Scientific Revolution in the European Periphery, Latin America and East Asia, edited by Celina A. Lértora Mendoza, Efthymios Nicolaidis, and Jan Vandersmissen (Turnhout: Brepols, 2000), 11–31.Ryan Tucker Jones, "Petr Simon Pallas, Siberia, and the European Republic of Letters," Istoriko-biologicheskie issledovaniia 3 no. 3 (2011): 55-67.Thomas Broman, "The Habermasian public sphere and 'science in the Enlightenment'," History of Science 36 (1998): 123-150.H. Otto Sibum, “Experimentalists in the Republic of Letters,” Science in Context 16, no. 1–2 (March 2003): 89–120. (And see other articles on "scientific personae" in this issue.)Mary Terrall, "Emilie du Châtelet and the Gendering of Science," History of Science 33 (1995): 283-310.William Clark, Jan Golinski, and Simon Schaffer, eds., The Sciences in Enlightened Europe (1999).

Michael D. Gordin, “The Importation of Being Earnest: The Early St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences,” Isis 91 (2000): 1–31.John Gascoigne, “The Eighteenth-Century Scientific Community: A Prosopographical Study,” Social Studies of Science 25, no. 3 (1995): 575–81.Dena Goodman, The Republic of Letters: A Cultural History of the French Enlightenment (1994). (NB: The sciences do not figure much in this account.)-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 8/01/25, 11:59

-

-

In this session we treat the vexed question of the relationship between science and politics in the age of the nation-state, beginning with the French Revolution. As early as April 1793 chemist Antoine Fourcroy sought to align the history of the natural sciences with the advancement of the French Republic: "France still retains the superiority that no other nation has so far refused her, and even since their glorious revolution, French savants have pushed back the limits of the human spirit more than the peoples bordering the Republic have done." How did the sciences contribute to the vaunting universalism of French revolutionary politics?

Since the French case becomes a reference point for all the others in the course of the nineteenth century, and because many French scientists attained positions of influence during the French Republic and Empire, I have prepared an introductory lecture to set the scene.

Assigned reading:

Francis William Blagdon, "Letter XXXIV," Paris As It Was and As It Is: or, A sketch of the French Capital, Illustrative of the Effects of the Revolution, with Respect to Sciences, Literature, Arts, Religion, Education, Manners, and Amusements; Comprising also a Correct Account of the Most Remarkable National Establishments and Public Buildings (1803), 391-397.

Patrice Higgonet, "Capital of science," Paris: Capital of the World (2002), 121-148.

French option: François (de Neufchâteau), "[Discours prononcé par François de Neufchâteau à l'ouverture de l'exposition des produits de l'industrie française]," Gazette nationale, ou le moniteur universel (1er Vendémiaire an 7 [1798]), 2. (Cf. transcription.)

German option: Johann Gottfried Schmeisser, "Vorrede," Beyträge zur näheren Kenntniß des gegenwärtigen Zustandes der Wissenschaften in Frankreich, vol. 1 (1797) v-xii.

Polish option: Roman Markiewicz, Paryż uważany co do nauk (1811).

Hungarian option: Kis János, “Mi segíti elő a tudományok és szép mesterségek virágzását?” Felső Magyar Országi Minerva 2, no. 4 (April 1825): 135–37.

Russian option: A. G. Glagolev, Записки русского путешественника А. Глаголева, с 1823 по 1827 год, vol. 4. (1837), 57-66.Suggested reading:

Maurice Crosland, “History of Science in a National Context,” British Journal for the History of Science 10, no. 2 (1977): 95–113.Maurice Crosland, The Society of Arcueil: A View of French Science at the Time of Napoleon I (1967).Robert Fox, The Savant and the State: Science and Cultural Politics in Nineteenth-Century France (2012).Robert Fox, The Culture of Science in France, 1700-1900 (1992).Dorinda Outram, Georges Cuvier: Vocation, Science, and Authority in Post-Revolutionary France (1984).Ludmilla Jordanova, “Science and Nationhood: Cultures of Imagined Communities.” In Imagining Nations (1998), edited by Geoffrey Cubitt, 192–211.George Lichtheim, “The Concept of Ideology” History and Theory 4, no. 2 (1965): 164–95.Matthew G. Adkins, “The Renaissance of Peiresc: Aubin-Louis Millin and the Postrevolutionary Republic of Letters,” Isis 99, no. 4 (2008): 675–700.Carol E. Harrison and Ann Johnson, “Introduction: Science and National Identity,” Osiris 24 (2009): 1–14.Carol E. Harrison, “Projections of the Revolutionary Nation: French Expeditions in the Pacific, 1791–1803,” Osiris 24 (2009): 33–52.L. Pearce Williams, “Science, Education and the French Revolution,” Isis 44, no. 4 (1953): 311–30.

Michel Serres, "Paris 1800," in Éléments d'histoire des sciences (1989), 337-361.

Keith Michael Baker, "Science and politics at the end of the Old Regime," Inventing the French Revolution: Essays on French Political Culture in the Eighteenth Century (1990), 153-166.Jessica Riskin, “Rival Idioms for a Revolutionized Science and a Republican Citizenry,” Isis 89, no. 2 (1998): 203–32.John Gascoigne, "The scientist as patron and patriotic symbol: The changing reputation of Sir Joseph Banks," in Telling Lives in Science: Essays on Scientific Biography, Shortland and Yeo, eds. (1996), 244-.Joseph Ben-David, "The rise and decline of France as a scientific centre," Minerva 2 (1970): 160-179.See also Adolphe Wurtz's famous polemic ("Chemistry is a French science."), Histoire des doctrines chimiques depuis Lavoisier jusqu'à nos jours (1868), best understood in combination with next week's session. (English, German, Polish; also translated by Butlerov into Russian)-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

-

“Anyone who is good at comparing the level of learning of Nations, penetrating the causes of civilization, does not deny that Germany owes its luminosity to the Naturforscher of its lands.” How did the politically fragmented German lands come to play such a central role in the rise of modern disciplinary science, and how did new forms of sociability in the natural sciences make Prussians, Saxons, and Bavarians “all become sons of one and the same mother—Germany”?

Since there is a surfeit of material on the German case, here is a short background lecture on the Congresses of German Nature Researchers and Physicians.

Assigned reading:

[Lorenz Oken], “[Congress of German naturalists and physicians in Leipzig on 18 September 1822],” Isis Encyclopädische Zeitung, no. 6 (1823): 549–59 (abridged). (Original German text.)"German Association, &c." The North American Review 31 (1830): 85-93.

Denise Phillips, "Introduction," Acolytes of Nature: Defining Natural Science in Germany, 1770-1850 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 1-26.German options: Alexander von Humboldt, Rede, gehalten bei der Eröffnung der Versammlung deutscher Naturforscher und Ärzte in Berlin, am 18. September 1828 (1828). (Or Polish version, p. 426)Emil du Bois-Reymond, "Ueber das Nationalgefühl" (1878).Polish option: “Wyjątek z listu pisanego z Berlina do Krzemieńca dnia 30 (18) septembra 1828 r.” Kuryer Litewski, no. 11 (January 25, 1829): 4.Czech option: Jan Presl, "[Translator's introduction]" to Georges Cuvier, Barona Jiřího Cuviera Rozprava o převratech kůry zemní, a o proměnách v živočistvu jimi způsobených, v ohledu přírodopisném a dějopisném (1834), i-viii.Hungarian option: Almási Balogh Pál, “A Német Természetvizsgálók és Orvosok Egyesűlete,” Hasznos mulatságok 1, no. 8 (1826): 57–61.Russian option: F. P. Lubianovskii, Zametki za granitseiu v 1840 i 1845 godakh (1845), 20-33.Baltic German option: Alexander Crichton, Joseph Rehmann, and Karl Friedrich Burdach, “Vorbericht,” Russische Sammlung für Naturwissenschaft und Heilkunst 1, no. 1 (1815): i–x.French option: Antoine Laurent Apollinaire Fée, 12.me Congrès scientifique. Stuttgart pendant l’automne de 1834 (1835).British option: Charles Babbage, “Account of the Great Congress of Philosophers at Berlin on the 18th September 1828,” Edinburgh Journal of Science 10, no. 2 (1829): 225–34.Suggested reading:

Kathryn M. Olesko, “Germany,” in Hugh Slotten, ed., Cambridge History of Science, 8 (2019): 233-277.Ralph Jessen and Jakob Vogel, eds., Wissenschaft und Nation in der europäischen Geschichte (2002).Kai Torsten Kanz, Nationalismus und internationale Zusammenarbeit in den Naturwissenschaften: Die deutsch-französischen Wissenschaftsbeziehungen zwischen Revolution und Restauration, 1789-1832 (1997).Science in Germany: The Intersection of Institutional and Intellectual Issues, Osiris 5 (1989).Myles W. Jackson, “A Spectrum of Belief: Goethe’s ‘Republic’ versus Newtonian ‘Despotism’,” Social Studies of Science 24, no. 4 (1994): 673–701.Michael Dettelbach, “Romanticism and Resistance: Humboldt and ‘German’ Natural Philosophy in Napoleonic France.” In Hans Christian Ørsted and the Romantic Legacy in Science: Ideas, Disciplines, Practices, edited by Robert M. Brain, Robert S. Cohen, and Ole Knudsen, 241:247–58. Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science. Dordrecht: Springer, 2007.William Clark, “On the Dialectical Origins of the Research Seminar,” History of Science 27 (1989): 111–54.R. Steven Turner, "University reformers and professorial scholarship in Germany 1760-1806," in The University in Society, vol. 2, ed. L. Stone (1974), 495-531.Charles E. McClelland, State, Society, and University in Germany, 1700-1914 (1980).Andreas W. Daum, Wissenschaftspopularisierung im 19. Jahrhundert: Bürgerliche Kultur, naturwissenschaftliche Bildung und die deutsche Öffentlichkeit, 1848–1914 (1998).

Harry W. Paul, The Sorcerer's Apprentice: The French Scientist's Image of German Science 1840-1919 (1972).Pierre Duhem, “Quelques réflexions sur la science allemande,” Revue des deux mondes 25 (1915): 657–86.-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

-

While the old political vision of "unity in diversity" failed in the Habsburg lands (with those failures giving rise to a vast historiography), the role of the natural sciences in local, national, and imperial dynamics has only become an object of sophisticated investigation comparatively recently. "The gathering of men of science from all lands of the empire, the striving toward common goals pursued along one among many diverse lines of research shows us an apt reflection of the unity of the great state to which we are proud to belong," proclaimed one German-speaking Austrian scientist in the 1850s. Yet many Austrian scientists were invested in something other than imperial unity, and we discuss recent work on the scale of their research and the mobility of their careers in order to see how the "expanding circles of scientific life" could mediate between Staatsnation and Kulturnation agendas.

Assigned reading:

"Toward an appreciation of intellectual life in Austria," Allgemeine Zeitung (July 6, 1860), Beilage zu Nr. 188 edition. [Original German text]

Deborah R. Coen, "The power of local differences," Climate in Motion: Science, Empire, and the Problem of Scale (2018), 170-204.

German options: “Das Fest der Naturforscher in Wien,” Zeitung für die elegante Welt (October 19, 1832).

Justus von Liebig, “Die Zustand der Chemie in Oestreich,” Annalen der Pharmacie 25, no. 1 (1838): 339–47.Joseph Hyrtl, “Einst und Jetzt der Naturwissenschaft in Österreich,” in Amtlicher Bericht über die zwei und dreissigste Versammlung Deutscher Naturforscher und Ärzte zu Wien im September 1856, edited by Joseph Hyrtl and Anton Schrötter (1858), 22-28.Polish option: Józef Dietl, “O instytucyi Docentów w ogóle, a szczególnie w Universytecie Jagiellońskim,” Czas (October 31, 1861).Hungarian option: “A tudomány támogatása,” Az ujság (March 10, 1911).If there is the right combination of interest and linguistic expertise, we could discuss J. E. Purkyně's Austria Polyglotta (1867), available in Czech and German versions.Suggested reading:

Tatjana Buklijas and Emese Lafferton, “Science, Medicine and Nationalism in the Habsburg Empire from the 1840s to 1918,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 38 (2007): 679–86.Mitchell G. Ash, “The Natural Sciences in the Late Habsburg Monarchy: Institutions, Networks, Practices,” in The Global and the Local: The History of Science and the Cultural Integration of Europe, edited by Michał Kokowski (2006), 380–83.Mitchell G. Ash and Jan Surman, eds., The Nationalization of Scientific Knowledge in the Habsburg Empire, 1848-1918 (2012). (See their introduction.)Jan Surman, “The Circulation of Scientific Knowledge in the Late Habsburg Monarchy: Multicultural Perspectives on Imperial Scholarship,” Austrian History Yearbook 46 (2015): 163–82.Török Borbála Zsuzsanna, Exploring Transylvania: Geographies of Knowledge and Entangled Histories in a Multiethnic Province, 1790-1918 (2016).Johannes Feichtinger, "'Staatsnation', 'Kulturnation', 'Nationalstaat': The role of national politics in the advancement of science and scholarship in Austria from 1848 to 1938," in Ash and Surman, Nationalization of Scientific Knowledge, 57-82.David N. Livingstone, Putting Science in Its Place: Geographies of Scientific Knowledge (2003).

Marianne Klemun, "National 'consensus' as culture and practice: The Geological Survey in Vienna and the Habsburg Empire (1849-1867)," in Ash and Surman, Nationalization of Scientific Knowledge, 83-101.Wolfgang L. Reiter, Aufbruch und Zerstörung: Zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften in Österreich 1850 bis 1950 (2017).Lewis Pyenson, “An End to National Science: The Meaning and the Extension of Local Knowledge,” History of Science 40 (2002): 251–90.-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

-

In the partitioned Polish lands scientists condemned small-spirited provincialism, calling instead for "the idea of great co-national harmony! And just as the nature of these lands which we have settled is bound amid its entire countless variety into one integral whole, so we will obey the eternal laws of nature, and combine various peoples, societies, and countries into one organic national whole, into one nation." Did natural science help unite the Poles?

Presentation: Oksana

Assigned reading:

Józef Majer, "The relation of the Cracow Scientific Society toward science and the country" (1868). [Polish source]

Jerzy Jedlicki, "Professional environments," in The Vicious Circle 1832-1864, vol. 2 of A History of the Polish Intelligentsia (2014), 163-190.

Polish options: Jan Śniadecki, “O języku narodowym w matematyce. Rzecz czytana na posiedzeniu Literackiem Universytetu Wileńskiego dnia 15. Listopada roku 1813. v. s.,” in Dzieła Jana Śniadeckiego, edited by Michal Baliński, 2nd ed. (Warsaw: A. E. Glücksberg, 1837), 3:194–210.

“Zjazd lekarzy i przyrodników w Krakowie,” Czas (September 14, 1869).Kornelius, “Znaczenie zjazdów naukowych i towarzyskich,” Sobótka tygodnik belletrystyczny illustrowany, no. 37 (September 9, 1871): 435–38.[Andrzej Niemojewski], “Dyskusja Galicyjska,” Myśl Niepodległa, no. 139 (July 1910): 913–27. (Cf. here (vol. 13, no. 3) for the object of his critique.)Jan K. Kochanowski, “Kilka słów w sprawie nauki narodowej,” Nauka polska 2 (1919): 444–48.Czech option: “Šestý sjezd lékařů a přírodozpytců polských v Krakově,” Živa 1, no. 9 (1891): 279–81.German option: “Bericht über die I. Jahres-Versammlung der polnischen Aerzte und Naturforscher,” Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift, no. 79 (October 2, 1869): 1327–29.Russian option: V. R. K., "Польские письма. Пятое письмо," Русская мысль no. 10 (1881): 34-41.Suggested reading:

Patrice M. Dabrowski, "Constructing a Polish landscape: The example of the Carpathian frontier," Austrian History Yearbook 39 (2008): 46-65.Magdalena Micińska, At the Crossroads 1865-1918, translated by Tristan Korecki, Vol. 3, A History of the Polish Intelligentsia (Frankfurt am Main, 2014).Antoni Karbowiak, Młodzież polska akademicka za granicą 1795-1910, (1910).Artur Kijas, Polacy w Rosji od XVII wieku do 1917 roku: Słownik biograficzny (2000).Zofia Skubała-Tokarska, ed., Historia nauki polskiej, vol. 4 (1987).Owen Gingerich, “The Copernican Quinquecentennial and Its Predecessors: Historical Insights and National Agendas,” Osiris 14 (1999): 37–60. (NB: There is a large literature in Polish and German on the anachronistic nationality of Copernicus. Please ask if you want references.)For a classic positivist account of Polish contributions to the sciences, see Feliks Konecny, ed., Polska w kulturze powszechnej, volume 2 (1918).-

Uploaded 10/01/25, 23:30

-

-

"In science," physicist Loránd Eötvös declared, "triumph even today still depends on heroes, not on the multitude of armies, and we need the kind of heroes who can conquer a country for us Hungarians in the world of science." The search for heroes, however, very much colored the disciplinary landscape in favor of language, literature, and law as preferred modes of scholarship in nationalizing Hungary. How did the natural sciences slowly lay claim to their place in this narrative?

Presentations: Botond, Laszlo

Assigned reading:

Loránd Eötvös, "[President's inaugural speech],"Akadémiai Értesítő, no. 6 (1895): 321–25. (Original Hungarian source.)Gábor Palló, “Scientific Nationalism: A Historical Approach to Nature in Late Nineteenth-Century Hungary,” in The Nationalization of Scientific Knowledge in the Habsburg Empire, 1848-1918, 102–12.Hungarian options: N. Takátsi Horváth János, "A tudományok ditsérete," Tudományos Gyűjtemény 18 (1834): 49-72.

Frivaldszky Imre, Javaslat a természettudományok felvirágoztatása ügyében (1844).

Nendtvich Károly, “Még egyszer: Tudomány és magyar tudós,” Új Magyar Muzeum 2, no. 1 (1851): 37–51.

E., “Magyar géniusz,” Budapesti Hírlap (February 22, 1887).

Bartucz Lajos, “A modern nemzeti tudományról,” Magyar Szemle 10 (1930): 329.Kornis Gyula, “Tudomány és nemzet,” Budapesti szemle 260, no. 761–762 (1941): 193–222, 347–61.Szily Kálmán, “Magyarország és a természettudományok,” Természettudományi Közlöny 10 (1878): 1–10.Than Károly, “Culturánk és a természetbuvárkodás,” Budapesti szemle 129 (1907): 321–39.German option: Kálmán Szily, “Unsere Thätigkeit auf dem Gebiete der Naturwissenschaften im letzten Jahrzehnt,” Literarische Berichte aus Ungarn 1 (1877): 196–223.Czech option: Panýrek, "Věda a národnost," Národní listy (13 March 1908), 10. Cf. response here a week later.Suggested reading:

Gábor Palló, Zsenialitás és korszellem: világhírű magyar tudósok (2004).George Magyar, “Science and Nationalism,” Scientia 113 (1978): 867–84.Magyary-Kossa Gyula, “Adatok a magyar géniusz biologiájához,” Athenaeum 11, no. 4–6 (1925): 73–102.-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

-

[7] February 20 - Between nations: Weights & measures, patents, and the International Association of Academies

"It is interesting that there is an effort among scientific experts to make a kind of really accomplished unity, which would however exclude politics," wrote Czech physicist Čeněk Strouhal about international weights, measures, and nomenclatures in 1909. "Here, unity is [ultimately] excluded, since it would mean the end of politics." We will explore how international scientific institutions could both exclude politics as well as reinforce national hierarchies in the sciences.

Assigned reading:

"Business meeting / Plan for the Foundation of an International Association of Learned Societies," Report of the National Academy of Sciences (1900): 13-18.

Peter Alter, “The Royal Society and the International Association of Academies 1897-1919,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 34, no. 2 (1980): 241–64.German option: Wilhelm von Hartel, “Die internationale Assoziation der Akademien,” Deutsche Revue 31, no. 3 (1906): 267–83.Hungarian option: Kemény Ferenc, “Világakadémia,” Athenaeum 10 (1901): 109–19, 273–88, 441–60, 565–86. (Parts 1 and 2 are enough for present purposes.)

Russian options: V. M. Bekhterev, "О сближении славянских народов на почве науки," Вестник Европы 44 (July 1909): 314-321. [begins with scan 320]

A. S. Famintsyn, "Первый съезд Международной ассоциации академий," Мир божий № 1 (1902): 158-172. [See alternate link]

Polish option: "W sprawie zjazdu lekarzy słowiańskich w Sofji," Kuryer Lwowski (7 July 1910): 10.

Czech options: Konst. Jiriček, "Z výletu do Paříže," Osvěta no. 7 (1901): 592-598.

"Sbratření velikých národů vědami," Naše doba 14 (1907): 605-607.

French option: Association internationale des Académies. Première assemblée générale tenue a Paris, du 16 au 20 Avril 1901 (1901).

Suggested reading:

Brigitte Schroeder-Gudehus, "International science from the Franco-Prussian War to World War Two: An era of organization," in Slotten, ed., The Cambridge History of Science vol. 8 (2020): 43-59.Michael Eckert, "Gelehrte Weltbürger: Der Mythos des wissenschaftlichen Internationalismus," Kultur & Technik no. 2 (1992): 26-34.Elisabeth Crawford, Crawford, T. Shinn, and Sverker Sörlin, Denationalizing Science: The Contexts of International Scientific Practice (1993).Martin Gierl, Geschichte und Organisation. Institutionalisierung als Kommunikationsprozess am Beispiel der Wissenschaftsakademien um 1900 (2004).Chris Manias, “The Race Prussienne Controversy: Scientific Internationalism and the Nation,” Isis 100 (2009): 733–57.Alfred Nordmann, “European Experiments,” Osiris 24 (2009): 278–302.George Sarton, “War and Civilization,” Isis 2 (1919): 315–21.-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

-

By the late nineteenth century the ethnically diverse scientists of the Romanov Empire came to embrace the social mechanism of Russian science: the school, "in the sense that research methods peculiar to scientists of Russian nationality, and that in many areas their own Russian schools have already been formed, schools which take their origin from scientists who are either of Russian nationality or from scientists of non-Russian origin active on Russian soil (thus there is a Russian medical school, there is a Russian chemical school, etc.), and in some areas these schools are evidently in the process of forming (in history, in philology). In this fashion there is undoubtedly a phenomenon at the present time which we consider ourselves entitled to call Russian science."

Presentations: Marina, Dmitrii

Assigned reading:

А. M. Butlerov, "[A Russian or only an Imperial Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg?]" (1882), in Сочинения, vol. 3 (1958), 118-138 (abridged). (Original Russian text.)

Michael D. Gordin, “Points Critical: Russia, Ireland, and Science at the Boundary” Osiris 24 (2009): 99–119.

Russian options: V. I. Modestov, Русская наука за последние двадцать пять лет (1890).

A. I. Vvedenskii, "Возможна ли национальность в науке?" (1900).

N. Kareev, "Мечта и правда о русской науке. (По случайному поводу, но не по случайной причине)," Русская мысль 5 no. 12 (1884): 100-135. (Concentrate on Part I and skim the rest.)

German option: "Russland," Allgemeine Zeitung (23 December 1880): 5264.

Suggested reading:

Daniel A. Alexandrov, “The politics of scientific ‘kruzhok’: Study circles in Russian science and their transformation in the 1920s,” in Na perelome: Sovietskaia biologiia v 20-30-kh godakh, edited by E. I. Kolchinskii, 255–67 (St. Petersburg, 1997).Research Schools: Historical Reappraisals, Osiris 8 (1993).

D. Gouzévitch, “Научная школа как форма деятельности,” Вопросы истории естествознания и техники, no. 1 (2003): 64–93.Karl Hall, “The Schooling of Lev Landau: The European Context of Postrevolutionary Soviet Theoretical Physics,” Osiris 23 (2008): 230–59.Michael D. Gordin, “The Heidelberg Circle: German Inflections on the Professionalization of Russian Chemistry in the 1860s,” Osiris 23 (2008): 23–49.Michael D. Gordin, A Well-Ordered Thing: Dmitrii Mendeleev and the Shadow of the Periodic Table (2004). (Cf. pp. 121-126 for his indispensable reading of Butlerov and the Mendeleev affair.) (By contrast, see the high-Stalinist view of the affair.)I. S. Dmitriev, "Скучная история (о неизбрании Д. И. Менделеева в Императорскую академию наук в 1880 г.)," Вопросы истории естествознания и техники 23 (2003): 231-280.Iu. A. Khramov, Научные школы в физике (1987).Marina V. Loskutova, “S"ezdy russkikh estestvoispytatelei i professorsko-prepodavatel’skii korpus universitetov rossiiskoi imperii (1860-1910-e gg.),” in Professorsko-prepodavatel’skii korpus rossiisskikh universitetov 1884-1917 gg., edited by M. V. Gribovskii and S. F. Fominykh (2012), 76–93.See also Olga Valkova's research on female participation in the Russian congresses of scientists and physicians.Loren R. Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor, Naming Infinity: A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity (2009).Andy Bruno, “A Eurasian Mineralogy: Aleksandr Fersman’s Conception of the Natural World,” Isis 107 (2016): 518–39.

Gerald Geison, Michael Foster and the Cambridge School of Physiology: The Scientific Enterprise in Late Victorian Society (1978).J. B. Morrell, “The Chemist Breeders: The Research Schools of Liebig and Thomas Thomson,” Ambix 19 (1972): 1–46.

Loren Graham, "Russia and the former USSR," in Hugh Slotten, ed., Modern Science in National, Transnational, and Global Context, vol. 8 in The Cambridge History of Science (2019), 278-304.-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

-

Nineteenth-century national discourses by and about Ukrainian scientists are particularly difficult to trace properly, not only due to bilingualism and the obvious division of constituencies across imperial boundaries, but also because in the Romanov Empire it has been almost exclusively Russianness that has been interrogated vis-à-vis the natural sciences. With reference to both the Shevchenko Society and the eventual founding of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences in Kiev, we will attempt to assess both the substance as well as the frequent question-begging in early imputations of Ukrainian science.

Presentation: Kateryna

Assigned reading:

Oleksandr Ianata, "Prospects for the development of natural science in Ukraine," Вісник природознавства [Herald of natural science] no. 1 (Kyiv, 1921): 7-13. (Original Ukrainian text; go to page 135.)

Jan Surman, “Science and Terminology In-between Empires: Ukrainian Science in a Search for Its Language in the Nineteenth Century,” History of Science 57 (2018): 260–87.Ukrainian options: E. M. Alyk, "Перша нарада природників України,"Літературно-науковий вісник 71 no. 7-8 (1918): 149-152.

Iv. Krevets'kyi, "Українська Академія Наук у Київі," Літературно-науковий вісник 77 no. 5 (1922): 139-149. Part 2 (no. 6, 251-257). Part 3 (78, no. 7, 63-71).

M. Ivaneiko, "Вартість науки," Літературно-науковий вісник 91 no. 12 (1926): 357-367.

O. Gol'dman, "[Physics in Ukraine on the 10th anniversary of Soviet Ukraine]," Вісник природознавства no. 5-6 (Kharkiv, 1927): 257-272.

Cherntsov, "[October and science in Ukraine]," Prapor marksizmu no. 5 (1929): 127-143.

Bonus material on Belarusian regional studies: M. Kas'piarovich, "Білоруське краєзнавство," Червоний шлях №7 (1.07.1928): 160-.

Russian options: История Харьковского Общества наук (1817).

M. A. Maksimovich, "О степенях сродства между наречиями" (1848).

V. I. Vernadskii, Дневники, 1917-1921, vol. 1 (1997). (Various reflections on Ukrainian politics and the creation of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences.)Polish option: "Towarzystwo imienia Szewczenki," Kuryer Lwowski (18 March 1892), 2-3.

German option: Johann Heinrich Blasius, "Reise durch die Ukraine," Reise im europäischen Russland in den Jahren 1840 und 1841, vol. 2 (Braunschweig: George Westermann, 1844), 286-306. [pp. 305-306 are the main passage of interest for present purposes.]

Suggested reading:

Kazimierz Twardowski, Die Universität Lemberg: Materialien zur Beurteilung der Universitätsfrage (Vienna, 1907).

Founding Statute of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, Державний вістник no. 75 (1918).

Anton Kotenko, The Ukrainian Project in Search of National Space, 1861-1914, PhD dissertation, CEU (2014).

T. Shcherban' and V. Onoprienko, Джерела з історії Українського наукового товариства в Києві (2008).

G. A. Doronina et al., "Створення Української академії наук у Києві в 1918 р.: хронологія подій," Наука та наукознавство no. 1 (2018): 92-113.

Volodymyr Gnatiuk, Наукове товариство імені Шевченка: З нагоди 50-ліття його засновання (1923).

Anhelina Korobchenko, "The value of the Naturalists Society at Kharkiv University (1869-1930) in the development of scientific research and the popularization of scientific knowledge in Ukraine," History of Science and Technology 9 (Kiev, 2019): 211-224.

Martin Rohde, “Local Knowledge and Amateur Participation. Shevchenko Scientific Society, 1892–1914,” Studia Historiae Scientiarum 18 (2019): 165–218.Martin Rohde, Nationale Wissenschaft zwischen zwei Imperien: die Ševčenko-Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften, 1892-1918 (2022).V. A. Kuchmarenko and V. G. Shmelov, "Українська Академіа наук у 1918-1927 рр.," Архіви України no. 4 (1992): 40-47. [available at www.libraria.ua]-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

-

Here again I lack expertise in this region, but students with relevant interests may press to include a session on science and the nation in Spain and Portugal. I will expand the bibliography after consultation with students eager to lead this session. In the meantime, here are some possibilities.

Presentation: Andres

Assigned reading:

Lino Camprubí and Thomas F. Glick, “Spain,” in Hugh Slotten, ed., Modern Science in National, Transnational, and Global Context, vol. 8 in The Cambridge History of Science (2019): 361–75.

Spanish option: Señor Don José Echegaray, "[Historia de las matemáticas puras en nuestra España], Discursos leídos ante la Real Academia de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales (Madrid, 1866). [suggested by a former student]

Further reading:

Mark Thurner and Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, eds., The Invention of Humboldt: On the Geopolitics of Knowledge (2023).Ana Simões and Maria Paula Diogo, “Portugal,” in Hugh Slotten, ed., Modern Science in National, Transnational, and Global Context, vol. 8 in The Cambridge History of Science (2019): 390–401.Ricardo Campos Marín and Rafael Huertas, “The Theory of Degeneration in Spain (1886-1920),” in The Reception of Darwinism in the Iberian World, Thomas F. Glick, Rosaura Ruiz, and Miguel Angel Puig-Samper, eds. (2001), 171–87. (Spanish edition)

Santos Casado and Santiago Aragón, “Vignettes of Spanish Nature: Imagining a National Fauna at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid (1910-1936),” Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 44 (2014): 197–233.Alberto Elena and Javier Ordóñez, “History of Science in Spain: A Preliminary Survey,” The British Journal for the History of Science 23 (1990): 187–96.Alberto Gil Novales, “Inquisición y Ciencia en el siglo XIX,” Arbor 124, no. 484 (1986): 147–170.

Alvaro Girón, “The Moral Economy of Nature: Darwinism and the Struggle for Life in Spanish Anarchism (1882-1914),” in The Reception of Darwinism in the Iberian World, Thomas F. Glick, Rosaura Ruiz, and Miguel Angel Puig-Samper, eds. (2001), 189-203.

Thomas Glick, Darwin en España (2010).Antonio Lafuente, and Tiago Saraiva, “The Urban Scale of Science and the Enlargement of Madrid (1851-1936),” Social Studies of Science 34 (2004): 531–69.Leoncio López-Ocón, “Ciencia e historia de la ciencia en el sexenio democrático. La formación de una tercera vía en la polémica de la ciencia española,” Dynamis 12 (1992): 87–104.

Agustí Nieto-Galan, “A Republican Natural History in Spain around 1900: Odón Buen (1863–1945) and His Audiences.” Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 42 (2012): 159–89. -

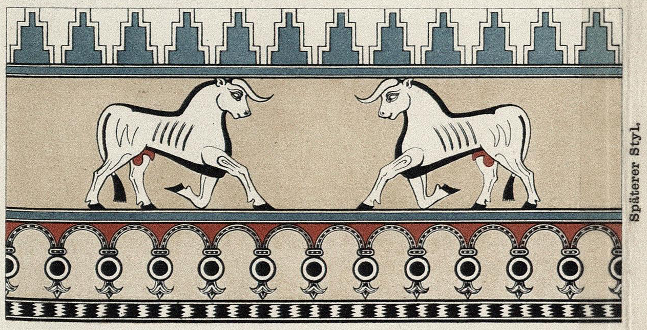

"To each insight, to each system of knowledge, to each entry into social relations corresponds its own reality," claimed Lwów bacteriologist Ludwik Fleck in 1929. "This is the only true point of view." Fleck was, in part, attempting to turn Heinrich Wölfflin's art-historical "style-as-physiognomy-of-epoch" in a more functionalist direction, but largely failed in his own day. Since Merz and Duhem, however, the urge to characterize national styles of science has retained its allure, and we will discuss the various attempts to link style concepts to the sociology of knowledge.

Presentation: Rajarshi

Assigned reading:

Ludwik Fleck, Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact (1979 [1935]), chapter 2. [Russian translation]

Claus Zittel, "Ludwik Fleck and the concept of style in the natural sciences," Stud. East Eur. Thought 64 (2012): 53-79.

Suggested reading:

Arnold Davidson, "Styles of reasoning, conceptual history, and the emergence of psychiatry," in The Disunity of Science, Galison and Stump, eds. (1996), 75-100.

Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Development of Style in Later Art, 7th ed. (1950 [1915]).

Michael Otte, “Style as a Historical Category,” Science in Context 4 (October 1991): 233–64.Anna Wessely, “Transposing ‘Style’ from the History of Art to the History of Science,” Science in Context 4, no. 2 (1991): 265–78.Alistair Crombie, Styles of Scientific Thinking in the European Tradition: The History of Argument and Explanation Especially in the Mathematical and Biomedical Sciences and Arts (1994).Alistair Crombie, “Commitments and Styles of European Scientific Thinking,” History of Science 33 (1995): 225–38.Ian Hacking, “Styles of Scientific Thinking or Reasoning: A New Analytical Tool for Historians and Philosophers of the Sciences.” In Trends in the Historiography of Science, edited by Kostas Gavroglu, Jean Christianidis, and Efthymios Nicolaidis, 31–48. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science (1994).Jonathan Harwood, Styles of Scientific Thought: The German Genetics Community, 1900-1933 (1993).Mary Jo Nye, “National Styles? French and English Chemistry in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries,” Osiris 8 (1993): 30–49.Axel Gelfert, "Art history, the problem of style, and Arnold Hauser's contribution to the history and sociology of knowledge," Stud. East Eur. Thought 64 (2012): 121-142.Deborah R. Coen, “Rise, Grubenhund: On Provincializing Kuhn,” Modern Intellectual History 9 (2012): 109–26."Dossier Ludwik Fleck," Transversal 1 (2016).Thomas Schnelle and R. S. Cohen, eds., Cognition and Fact: Materials on Ludwik Fleck, Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science (1986).

Robert Fox, "The rise and fall of Laplacian physics," Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 4 (1974): 89-136.

[click on image for source]-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

-

"The scientist today cannot practice his calling in isolation," wrote Hungarian chemist Michael Polanyi in 1942. "He must occupy a definite position within a framework of institutions. A chemist becomes a member of the chemical profession; a zoologist, a mathematician or a psychologist—each belongs to a particular group of specialized scientist. The different groups of scientists together form the scientific community." Jewish and twice exiled, Polanyi did not invariably appeal to the global fungibility of the scientific community and its universal ideas, but was more intent on establishing the conditions of its "self-government." Its formation was constrained by history, culture, and tradition.

Discussion leader: Laszlo

Michael Polanyi, "The autonomy of science" The Scientific Monthly 60 (1945 [1943]): 141-150.

Thomas S. Kuhn, "Progress through revolutions," The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), 160-173. [Numerous copies available in library: 501 KUH.]

Suggested reading:

Robert K. Merton, “A note on science and democracy,” Journal of Legal and Political Sociology 1 (1942): 115–126.

Mary Jo Nye, Michael Polanyi and His Generation: Origins of the Social Construction of Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).Struan Jacobs, “Models of Scientific Community: Charles Sanders Peirce to Thomas Kuhn,” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 31, no. 2 (June 1, 2006): 163–73.Grigorii Iudin, "Иллюзия научного сообщества," Sotsiologicheskoe obozrenie 9 no. 3 (2010): 57-84.Chad Wellmon, Organizing Enlightenment: Information Overload and the Invention of the Modern Research University (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge (1958).Michael Polanyi, “The Republic of Science: Its Political and Economic Theory,” Minerva 1 (1962): 54–73.Philip Mirowski, “On Playing the Economics Trump Card in the Philosophy of Science: Why It Did Not Work for Michael Polanyi,” PSA Proceedings 64 (1997): S127–38.Florian Znaniecki, “Przedmiot i zadania nauki o wiedzy,” Nauka polska 5 (1925): 1–78.Max Scheler, Die Wissensformen und die Gesellschaft (1926).-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:15

-