Intellectuals and World War I (Fall 2024)

Section outline

-

Instructor: Karl Hall

Number of credits: 4

Course level: Masters

Time: Mondays at 15:40 and Thursdays at 13:30

Location: A201 and A214

Instructor's office hours: Monday 13:30-15:30; Wednesday 14:00-15:00; Thursday 11:30-12:30; and by appointment

Zoom option: If you require Zoom access for health reasons, etc., use this link. Please alert the instructor beforehand if you will not attend in person; online access is not automatic.

On the eve of the First World War the educated classes of the Habsburg and Romanov Empires remained a tiny elite, even if the universities had begun to facilitate upward social mobility, and more functions for the "intellectual" were gradually taking form. This course explores themes connecting intellectuals and the formative experiences of the wider European war. The "mobilization of intellect" involved more than literary figures offering patriotic rationales for victory. We seek to understand how the war accelerated prior trends or initiated new ones in various cultural domains, and what legacies the war had for intellectual life after Trianon and Brest-Litovsk.In this course we will spend most of our time on the "home front." It is true that many intellectuals became cannon fodder at the front, and on occasion this would later feed into growing popular cynicism about how the war was being prosecuted. But intellectuals qua soldiers are marginal to our enterprise here, while at the same time we need to understand that their domestic roles extended beyond sustaining (or, more rarely, criticizing) ruling and/or popular views of the war. The war haltingly facilitated new forms of expertise, even if it did not yield a total mobilization in this respect. But insofar as the war contributed to our understanding of the role of the intellectual in modern society, we shall cast our nets widely.

A few caveats: political, diplomatic, and military history are marginal to this course. And even insofar as our focus is on culture, I take it as crucial to the objectives of this course that we study more than "high culture" and the avant-garde. Our focus will be on Central and Eastern Europe, and reference to the British and French experiences will largely be limited to any historiographical lessons we might take from the vast literature on the Western Front. The German (not to say Austrian) case will loom somewhat larger for pragmatic reasons, if only because a larger secondary literature in English can provide us with points of entry for topics still inadequately represented in English for the regional languages that concern us. Where possible we will make use of Russian, Czech, Polish, Austrian, Hungarian, and Ukrainian readings as crucial to the scope of the course.

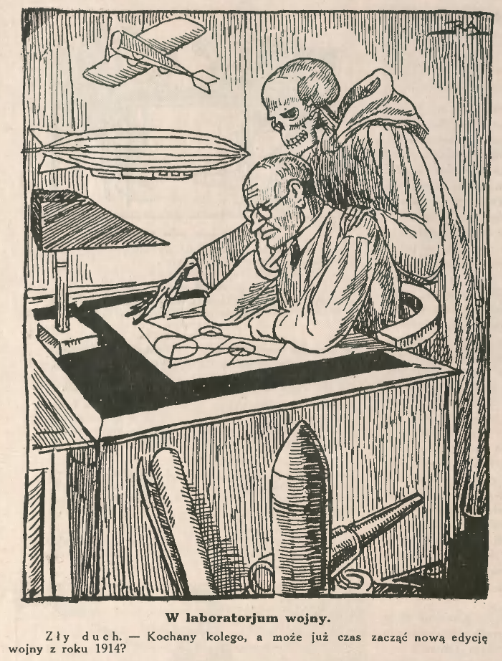

A few caveats: political, diplomatic, and military history are marginal to this course. And even insofar as our focus is on culture, I take it as crucial to the objectives of this course that we study more than "high culture" and the avant-garde. Our focus will be on Central and Eastern Europe, and reference to the British and French experiences will largely be limited to any historiographical lessons we might take from the vast literature on the Western Front. The German (not to say Austrian) case will loom somewhat larger for pragmatic reasons, if only because a larger secondary literature in English can provide us with points of entry for topics still inadequately represented in English for the regional languages that concern us. Where possible we will make use of Russian, Czech, Polish, Austrian, Hungarian, and Ukrainian readings as crucial to the scope of the course.Caption: In the laboratory of war

Evil spirit: “Dear colleague, perhaps it’s time to start a new edition of the war from the year 1914?”

Mucha (Warsaw, 1929)

Requirements and assessment: 12-15-page (double-spaced) research paper (40%); annotated bibliography (10%); class presentation (20%); discussion leader (10%); class participation (20%)

Annotated bibliography due November 25

Research paper due December 20

Learning outcomes: Students will gain a working acquaintance with the role of a variety of forms of expertise in the depiction and prosecution of the first world war, with special emphasis on intellectuals from Central and Eastern Europe. Our aim is to introduce students already familiar with the main outlines of the immensely rich historiography of the Great War to fresh avenues of approach that can contribute to a more sophisticated understanding of the intellectual legacies of this conflict.

Class Attendance: Regular attendance is mandatory in all classes. Please consult student handbook for the applicable rules and penalties.

With an appropriate research paper topic this course counts toward the Advanced Certificate in Central European Studies.

-

Opened: Thursday, 19 December 2024, 12:00 AMDue: Friday, 20 December 2024, 11:59 PM

You may upload your research paper here.

-

Assigned reading:

Karl Mannheim, "The problem of generations," in Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge (1952 [1927]), 276-320.

Additional resources:

Stephen Lovell, “Introduction,” in Generations in Twentieth-century Europe (2007): 1-18.

Stephen Lovell, "From genealogy to generation: The birth of cohort thinking in Russia," Kritika 9 (2008): 567-594.

Robert Wohl, The Generation of 1914 (1979).

Please make an effort to complete the reading in time for the first class meeting!

-

Assigned reading:

Jan Wacław Machajski (A. Vol'skii), excerpts from The Intellectual Worker (1904–1905), in The Making of Society: An Outline of Sociology, ed. V. F. Calverton (1937), 427–436.

Jan Wacław Machajski (A. Vol'skii), excerpts from The Intellectual Worker (1904–1905), in The Making of Society: An Outline of Sociology, ed. V. F. Calverton (1937), 427–436.Max Weber, "Science [scholarship] as a vocation" (1918), From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, eds. Hans Gerth and C. Wright Mills (New York, 1948 [1998]), 129–156.

Image: Max Weber in 1917 (Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz)

-

Assigned reading:

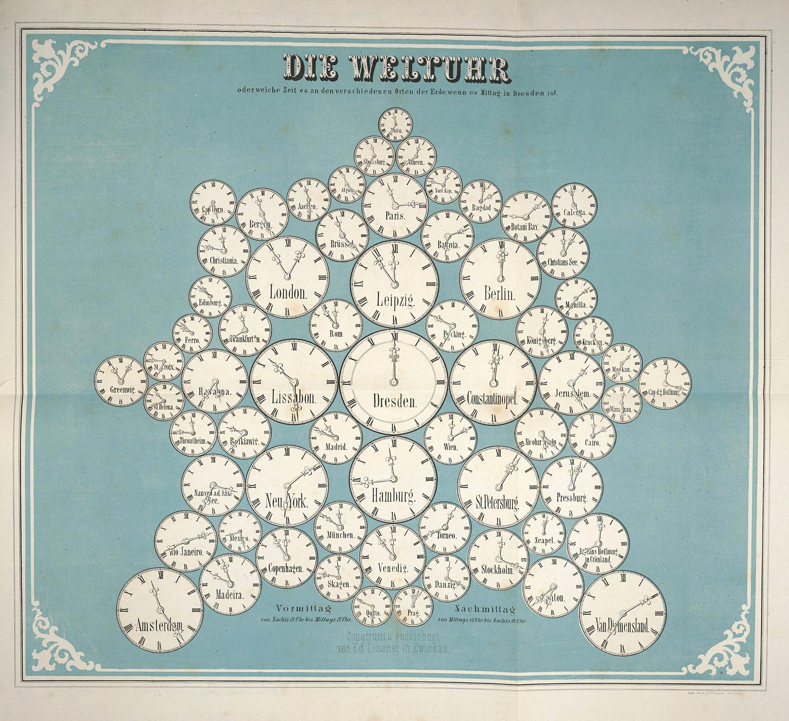

David Stevenson, "War by Timetable? The Railway Race before 1914," Past and Present 162 (1999): 163-194.

David Stevenson, "War by Timetable? The Railway Race before 1914," Past and Present 162 (1999): 163-194.Peter Galison, Einstein's Clocks, Poincaré's Maps (2004), 84-107, 155-161.

Additional resources:

Stephen Kern, “Temporality of the July Crisis,” The Culture of Time and Space 1880–1918 (1983), 259–312. [303.4/83 KER]

Anthony Heywood, "Spark of Revolution? Railway Disorganisation, Freight Traffic and Tsarist Russia's War Effort, July 1914–March 1917," Europe-Asia Studies 65 (2013): 753-772.

Keir A. Lieber, War and the Engineers: The Primacy of Politics over Technology (2005).

Daniel Pick, War Machine: The Rationalisation of Slaughter in the Modern Age (1993).

-

Assigned reading:

Readings taken from Between Worlds: A Sourcebook of Central European Avant-Gardes, 1910-1930, eds. Timothy O. Benson and Éva Forgács (2002):

Lajos Kassák, "Program" (1916) [Original Hungarian text in A Tett.]

Lajos Kassák, "Program" (1916) [Original Hungarian text in A Tett.]

Vlastislav Hofman, "The spirit of change in visual art" (1914)

Béla Balázs, "The futurists" (1912) [Original Hungarian text in Nyugat.]

Bruno Jasieński, "To the Polish nation: A manifesto concerning the immediate futurization of life" (1921) [Original Polish text.]S. A. Mansbach, "Methodology and meaning in the modern art of Eastern Europe," in T. O. Benson, ed., Central European Avant-Gardes: Exchange and Transformation, 1910-1930 (2002), 289-303. [NB: Mansbach barely mentions the war, but his revisionist critique should provide some structure to our discussion of the primary sources. Be prepared in class to speculate more than Mansbach does about the relation of the war to the historical location of the art historical modes of explanation he describes.]

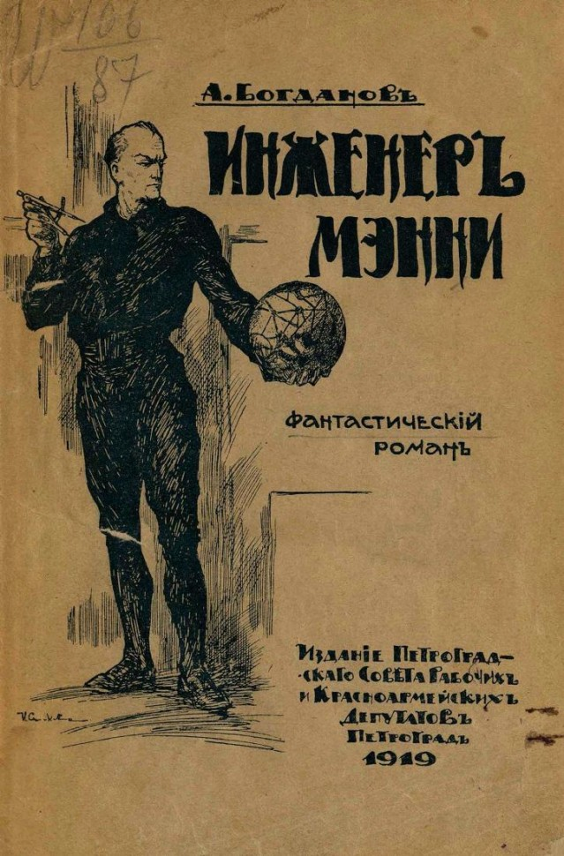

Image: Some modernist typography of "The Great War"; click to see original Russian document

An early Hofman furniture set:

[Source]

-

Assigned reading:

A. Kruchenykh, "Declaration of the word as such" (1913).

V. Mayakovsky, "A drop of tar" (1915), both in Words in Revolution: Russian Futurist Manifestoes (2004).

Kazimir Malevich, "From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The new painterly realism" (1915), in John Bowlt, ed., Russian Art of the Avant Garde: Theory and Criticism, 116-135.

Lev Ornstein, "Suicide in an Airplane"

Marjorie Perloff, "The Great War and the European avant-garde," Cambridge Companion to the Literature of the First World War (2006).

Further resources:

A. Koptiaev, "At the futurists' 'opera'" (1913), from Bartlett and Dadswell, Victory Over the Sun: The World's First Futurist Opera (2012).

Roman Jakobson, "Futurism" (1919), in Language in Literature, K. Pomorska and S. Rudy, eds. (1987), 28–33.

Image: Bohumil Kubišta, "Heavy artillery in action" (1913)

-

Uploaded 26/09/24, 16:26

-

Assigned reading:

"To the civilized world. An appeal" (1914) [Original German text.]

"To the civilized world. An appeal" (1914) [Original German text.]“Go ye and teach…” Budapesti Hírlap no. 248 (7 October 1914) [Original Hungarian text via Arcanum.]

S. Kotliarevskii, “War,” Journal of Philosophy and Psychology [Moscow] no.124 (September-October 1914), I-VII. [Original Russian text.]

Aleksej M. Rutkevic, "The ideas of 1914," Stud. East Eur. Thought (2014). [on-campus access only]

Additional resources:

Ernst Troeltsch, “On standards for assessing historical matters," Historische Zeitschrift 116 (1916): 1-47 (brief excerpts) [Original German text.]

Walther Schücking, Die deutschen Professoren und der Weltkrieg (1915).

Rudolf Kjellén, Die Ideen von 1914: Eine weltgeschichtliche Perspektive (1915).

Hermann Kellermann, Der Krieg der Geister (1915).

Hans Wehberg, Wider den Aufruf der 93! Das Ergebnis einer Rundfrage an die 93 Intellektuellen über die Kriegsschuld (1920). [available via North American VPN]

Anne Rasmussen, "Mobilizing minds," The Cambridge History of the First World War, vol. 3 (2013). [on-campus access only]

Tomasz Pudlocki and Kamil Ruszala, eds., Intellectuals and World War I: A Central European Perspective (2018). [940.3/1 PUD]

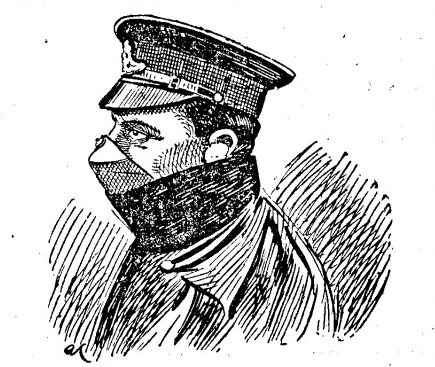

[click on image to enlarge] Caption: The War Poet

“Alright, we would at last appear to have the rhyme scheme for the first verse: …

[martial rhyming pairs]

Now it is just the rest of the connecting text that is lacking.”

Die Muskete [Vienna] (17 December 1914)

-

Assigned reading:

Aladár Schöpflin, "The war of words," Nyugat no. 20 (October 1914) [Original Hungarian text]

Aladár Schöpflin, "The war of words," Nyugat no. 20 (October 1914) [Original Hungarian text]Mikhail Rostovtsev, "International scientific communication," Russkaia mysl' bk. 3 (1916): 74-81. [original Russian text]

Karl Kraus, "The technoromantic adventure" (1918) [Original German text]

Image: "Now we do it simply and cleanly: press a button, trigger a mine – and thousands of children and adults are gone."

Novyi Satirikon (1915)

-

Assigned reading:

Max Scheler, “Table of categories of English thought,” from Der Genius des Krieges und der Deutsche Krieg [The Genius of War and the German War] (1915), 442-443.

Max Scheler, “Table of categories of English thought,” from Der Genius des Krieges und der Deutsche Krieg [The Genius of War and the German War] (1915), 442-443.Wilhelm Jerusalem, The War in Light of Social Theory (1915), 1-20. [original German text here]

Vladimir Ern, "From Kant to Krupp" (1914). [original Russian text here]

Additional resources:

Christopher Stroop, "Nationalist War Commentary as Russian Religious Thought: The Religious Intelligentsia's Politics of Providentialism," Russian Review 72 (2013): 94-115. [on campus only]

Daniel R. Huebner, "Wilhelm Jerusalem's sociology of knowledge in the dialogue of ideas," Journal of Classical Sociology 13 (2013): 430-459. [on campus only]

Randall A. Poole, "Religion, War, and Revolution: E. N. Trubetskoi's Liberal Construction of Russian National Identity, 1912–20," Kritika 7 (2006): 195-. [on campus access]

Thomas Baldwin, "Philosophy and the first world war," The Cambridge History of Philosophy, 1870-1945 (2008), 365-378. [on-campus access] [Anglocentric, but does discuss the crucial case of Wittgenstein]

-

Please choose one text and prepare to present it for 4-5 minutes in class. (We will agree on the distribution beforehand.)

Czech: Edvard Beneš, "Válka a kultura," Lumír (23 April, 28 May 1915).

Frant. Krejčí, "Právo eksistence malého národa," Česká mysl no. 3 (1915): 225-240.

Hungarian: Kornis Gyula, "A háborús filozófia," Athenaeum 2 (1916): 97-140.

Polish: Solomon Besser, Wojna evropejska jak walka ducha (1915).

Russian: Sergei Bulgakov, "Война и русское самосознание" (1915).

Semen Frank, "Мобилизация мысли в Германии," Русская мысль no. 9 (1916): 20-27.

Ukrainian: Dmytro Chyzhevs'kyi, "[The problem of national philosophy]," Філософія на Україні: спроба історіографії (1926), 9-14. [Not contemporary, but clearly written with the wartime experience in mind.]

Slovenian: Gregor Čremošnik, "Vasićeva knjiga »Karakter i mentalitet jednog pokolenja«," Ljubljanski zvon 40 no. 1 (1920): 59-61.

German: Magnus Hirschfeld, Warum hassen uns die Völker? (1915).

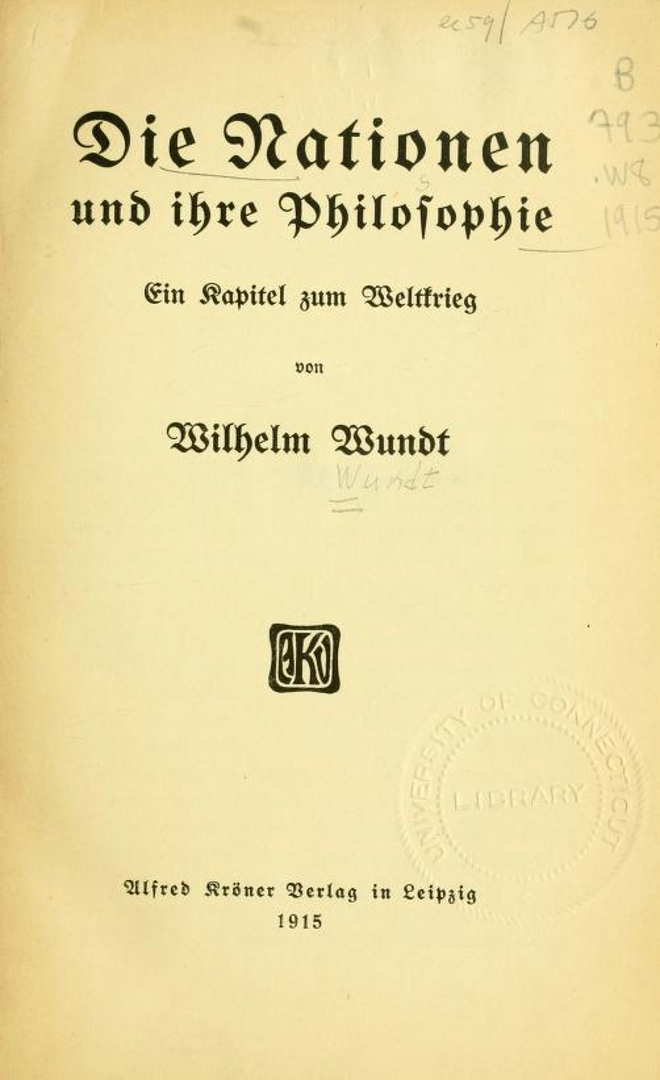

Wilhelm Wundt, "Der Geist der Nationen im Krieg und im Frieden," Die Nationen und ihre Philosophie (1915), 116-146.

German (Austrian): Othmar Spann, Zur Soziologie und Philosophie des Krieges. Vortrag im "Verband deutsch-völkischer Akademiker" zu Brünn (1912).

French: Émile Durkheim, L'Allemagne au dessus de tout : la mentalité allemande et la guerre (1915). [English translation]

Teilhard de Chardin, Écrits du temps de la guerre (1975). [temporarily unavailable]

English [French]: Émile Boutroux, "German science," in Philosophy and War (1916). [French text]

English: J. H. Muirhead, German Philosophy in Relation to the War (1915).

English: Leon J. Cole, "Biological philosophy and the war," The Scientific Monthly 8 (1919): 247-257.

-

Uploaded 11/10/24, 16:51

-

Optional background reading: Alison Frank Johnson, "Blood of the earth: The crisis of war," Oil Empire: Visions of Prosperity in Austrian Galicia (2005), 173-204. [This is not treating a contemporary intellectual debate as such, and will not directly inform our discussion, so you may read "efficiently." But it is an excellent account of the wartime economic context, and in general a book you should note.]

Optional background reading: Alison Frank Johnson, "Blood of the earth: The crisis of war," Oil Empire: Visions of Prosperity in Austrian Galicia (2005), 173-204. [This is not treating a contemporary intellectual debate as such, and will not directly inform our discussion, so you may read "efficiently." But it is an excellent account of the wartime economic context, and in general a book you should note.]Assigned reading:

Walther Rathenau, "The organization of raw materials supply" (1915) [German original]

V. I. Vernadskii, "War and the progress of science" (1915). [Russian original]

-

Class will be in room B-215.

Assigned reading:

Prof. Iar. Przheborovskii [Przeborowski], “Achievements of chemistry during the world war,” Krasnaia nov’ no. (1922): 301-309. [Original Russian text]

Prof. Iar. Przheborovskii [Przeborowski], “Achievements of chemistry during the world war,” Krasnaia nov’ no. (1922): 301-309. [Original Russian text]Jeffrey Johnson, "Military strength and science come together: The Kaiser's chemists at war," from The Kaiser's Chemists: Science and Modernization in Imperial Germany (1990), 180-199.

Suggested reading:

Ilosvay Lajos, "Az ellenséges nagy államok természettudományos mozgalmai a chemiai ipar fejlesztése érdekében," Természettudományi Közlöny no. 693-694 (1918): 145-167.

Fritz Haber, Fünf Vorträge aus den Jahren 1920 - 1923 (1925).

L. F. Haber, The Poisonous Cloud: Chemical Warfare in the First World War (1986).

Nathan M. Brooks, "Munitions, the military, and chemistry in Russia," in MacLeod and Johnson, eds., Frontline and Factory: Comparative Perspectives on the Chemical Industry at War, 1914-1924, Archimedes 8 (2006): 75-102.

Alexei Kojevnikov, "The Great War and the invention of Soviet science," Stalin's Great Science (2004), ch. 1.

-

Uploaded 21/10/24, 15:11

-

Presentation: Dylan

Assigned reading:

Maureen Healy, "Food and the politics of sacrifice," Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire: Total War and Everyday Life in World War I (2004): 31-72.

Maureen Healy, "Food and the politics of sacrifice," Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire: Total War and Everyday Life in World War I (2004): 31-72. Further reading:

Hedwig Heyl, Kleines Kriegskochbuch (1914).

Alfred Maylander, "Food situation in Central Europe, 1917" Bulletin of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics no. 242 (1918).

Belinda J. Davis, Homes Fires Burning: Food, Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin (2000).

Claire Morelon, "Black markets, green expeditions: Food shortages and growing divisions," in Streetscapes of War and Revolution: Prague, 1914-1920 (2024).

Lars T. Lih, Bread and Authority in Russia, 1914-1921 (1990).

Iaroslav Golubinov, "Food and nutrition (Russian Empire)," International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

Ernst Langthaler, "Food and nutrition (Austria-Hungary)," International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

Melanie Schulze-Tanielian, "Food and nutrition (Ottoman Empire/Middle East)," International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

Image: "The dance around the golden calf" [click to enlarge]

-

No classes this week.

-

Class will be in room B-215.

Choose ONE primary source to present in class:

Jaroslav Kříženecký, "O smrti hladem a porušování organismu nedostatečnou výživou," Lidove rozpravy lékařské 144 (1918): 3-36.

Julius Stoklasa, "Výživa obyvatelstva ve válce!" Ročnik agrární revue 2 (1916).

Ereky Károly, "Technikai tudományok a közélelmezés szolgálatában," and "Biotechnológia," MMEEK 52 (1918): 137-138, 337-339.

J. Mańkowski, Dwa systemy: szkic z dziedziny aprowizacji Królestwa Polskiego (1917).

Ludwig Nordeck zur Rabenau, Die Kriegsernährungswirtschaft in Österreich (1918).

H. Kuttenkeuler, "Nahrungsmittelchemie und Nahrungsmittelkontrolle im Kriege," Die Naturwissenschaften 28 (1917): 469-473.

M. Kudrits'kyi, "review of Гр. Коваленко, Анатомія і фізіологія людини в популярнім огляді," Книгар no. 19 (1919): 24-26. [Yes, it's slightly off topic, but try to make the connection.] [This site does not favor permanent links, so you will have to use the citation starting from the home page of libraria.ua.]

N. Orlov, Prodovol'stvennaia rabota Sovetskoi vlasti. K godovshchine oktiabr'skoi revoliutsii (1918). Concentrate on "Nasledstvo" (3-18) and "Khoziaistvennyi razval i proletarskaia diktatura," (40-55).

M. P. Fedorov, Prodovol'stvie Petrograda za vremia voiny (1915).

N. D. Kondratiev, Рынок хлебов и его регулирование во время войны и революции (1922).

Harvey W. Wiley, "Food and efficiency," Records of the Columbia Historical Society 20 (1917): 1-18.

Ernest B. Roberts, "What is food control?" (1918).

Ernest H. Starling, "The food supply of Germany during the war," Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 83 (1920): 225-245.

Herbert Hoover, "Food in war" [1918].

-

Classroom: A201

Presentation: Nikoletta

Assigned reading:

Roger Cooter and Steve Sturdy, "Of war, medicine and modernity: Introduction," in War, Medicine and Modernity (1998), 1-22.

Roger Cooter and Steve Sturdy, "Of war, medicine and modernity: Introduction," in War, Medicine and Modernity (1998), 1-22.Choose ONE text to present in class:

Emil Grósz, "Az orvosi tudomány a háborúban," Budapesti szemle 161 (1915): 75-83. [on-campus access only]

David John Davis, "Bacteriology and the war," The Scientific Monthly 5 (1917): 385-399.

Bailey K. Ashford, "The application of sanitary science to the Great War in the zone of the Army," Proc. Amer. Phil. Soc. 58 (1919): 317-336.

Tivadar Saile [Szél], "A bejelentésre kötelezett fertőző betegségek nemzetközi összehasonlítása. (1919-23)," Statisztikai szemle no. 1-4 (1925): 16-32.

Karl Kassowitz, "Der österreichisch-ungarisch Truppenarzt an der Front," in Clemens Pirquet, ed., Volksgesundheit im Krieg (1926), 133-142.Jan Piltz, "Zaburzenie nerwowe i psychiczne, spostrzegane podczas mobilizacji i w chasie wojny," Przegląd lekarski no. 3 (1915): 40-44.

V. M. Bekhterev, "Voina i psikhozy," Voprosy mirovoi voiny (1915), 590-604.

Further reading:

John F. Hutchinson, Politics and Public Health in Revolutionary Russia, 1890-1918 (1990), 108-143.

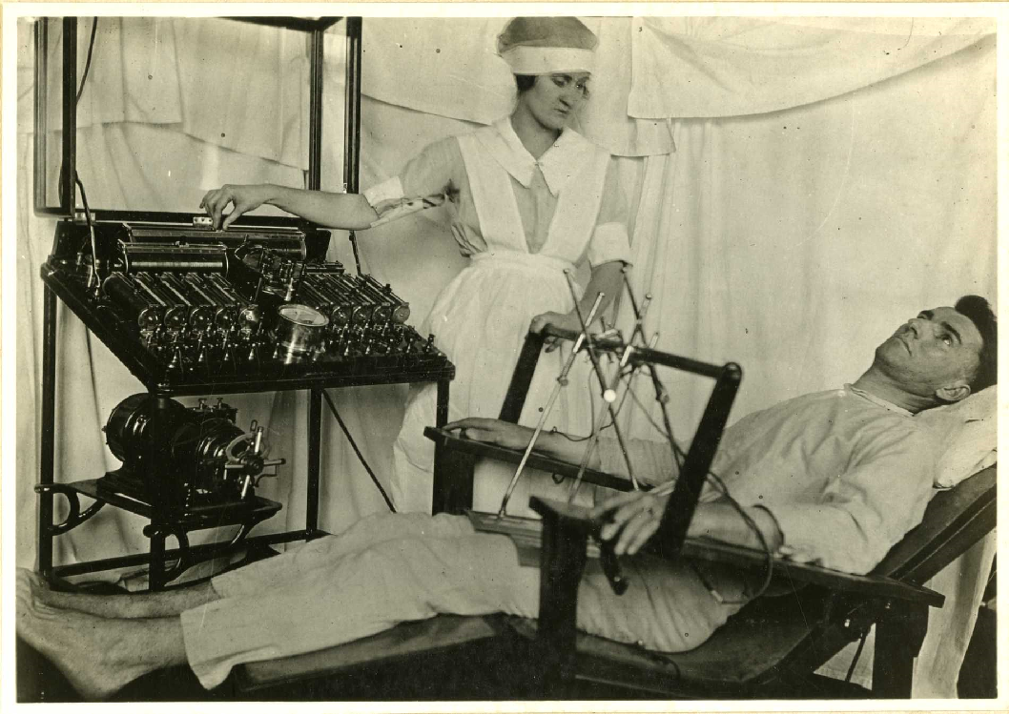

Image: X-ray field station

-

Class will be in room A-201.

Assigned reading:

Isaac Babel, "My first goose," from Red Cavalry Stories.

Isaac Babel, "My first goose," from Red Cavalry Stories.S. Ferenczi, "Two types of war neuroses" (1916), from Selected Writings.

From the special issue of Journal of Contemporary History devoted to "shell shock":

a: Merridale : Anton, Sofia, Marina

b: Leed : Camille, Niki, Matt

c: Mosse : Anil, Osman, Rajarshi

d: Lerner : Dylan, Lukas

Further reading:

Buday Dezső, "A haború hatása a szellemi munkára," Természettudományi Közlöny (1917), 635-639.

-

The war in the air hydrodynamic fluids

Please plan to arrive at the front entrance to the Museum of Technology at 11:30 on Saturday. (Allow time to take tram 60 from the Westbahnhof.) We will briefly visit two sections of the museum, and Matt will then make a presentation. We'll then retreat to the cafe to discuss the readings. (Caffeinated beverages are my treat.) You might want to bring a snack to leave in the lockers, have a bite after we disperse, and then return to visit other parts of the museum.

Assigned reading:

Scott W. Palmer, "The Russian warrior" and "The marasmus of Imperial aviation" and ""The air fleet is the strength of Russia," in Dictatorship of the Air: Aviation Culture and the Fate of Modern Russia (2006), 56-76. [on-campus only]

Scott W. Palmer, "The Russian warrior" and "The marasmus of Imperial aviation" and ""The air fleet is the strength of Russia," in Dictatorship of the Air: Aviation Culture and the Fate of Modern Russia (2006), 56-76. [on-campus only]Theodor von Kármán, “War, technology, science,” Pester Lloyd (18 October 1914): 2-3. [original German text] [Hungarian alternative] [see this simulation of the von Kármán vortex street]

David Bloor, The Enigma of the Aerofoil: Rival Theories in Aerodynamics, 1909-1930 (2011), 1-8, 410-412.

[click to enlarge]

-

Monday: A201

Lecture: Daryna

Presentations: Rajarshi, Sofia

Thursday: A214

Presentation: Camille

Assigned reading:

Monday:

Monday:Gustave Le Bon, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1909), 41-47; 56-66.

W. Trotter, "Prejudice in time of war," from Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War (1919), 214-224.

Sigmund Freud, Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1919), 41-52; 79-89. [original text available here]

Emile Durkheim, "Conclusion" (excerpt), The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, 444-448.

Daniel Pick, "Freud's Group Psychology and the history of the crowd," History Workshop Journal 40 (1995): 39-61.

Thursday:

Questionnaire from War and the Kostroma countryside (according to data of the Statistical Department’s questionnaire) (1915), 140–142.

Peter Holquist, "'Information is the alpha and omega of our work': Bolshevik surveillance in its pan-European context," J. Mod. Hist. 69 (1997): 415-450.

Further reading:

Eduardo Cintra Torres, "Durkheim's concealed sociology of the crowd," Durkheimian Studies / Études Durkheimiennes 20 (2014): 89-114.

István Dékány, "Tételek és paradoxonok a közvélemény problémájához," Társadalomtudomány 1 (1921): 242-247.

Ludwig Krašković, Die Psychologie der Kollektivitäten (1915).

Stefan Jonsson, "The revolving nature of the social: Primal hordes and crowds without qualities," Crowds and Democracy: The Idea and Image of the Masses from Revolution to Fascism (2013), 119-141.

David Hoffmann, "Surveillance and propaganda," in Cultivating the Masses: Modern State Practices and Soviet Socialism, 1914-1939 (2011).

Ferdinand Tönnies, Kritik der öffentlichen Meinung (1922).

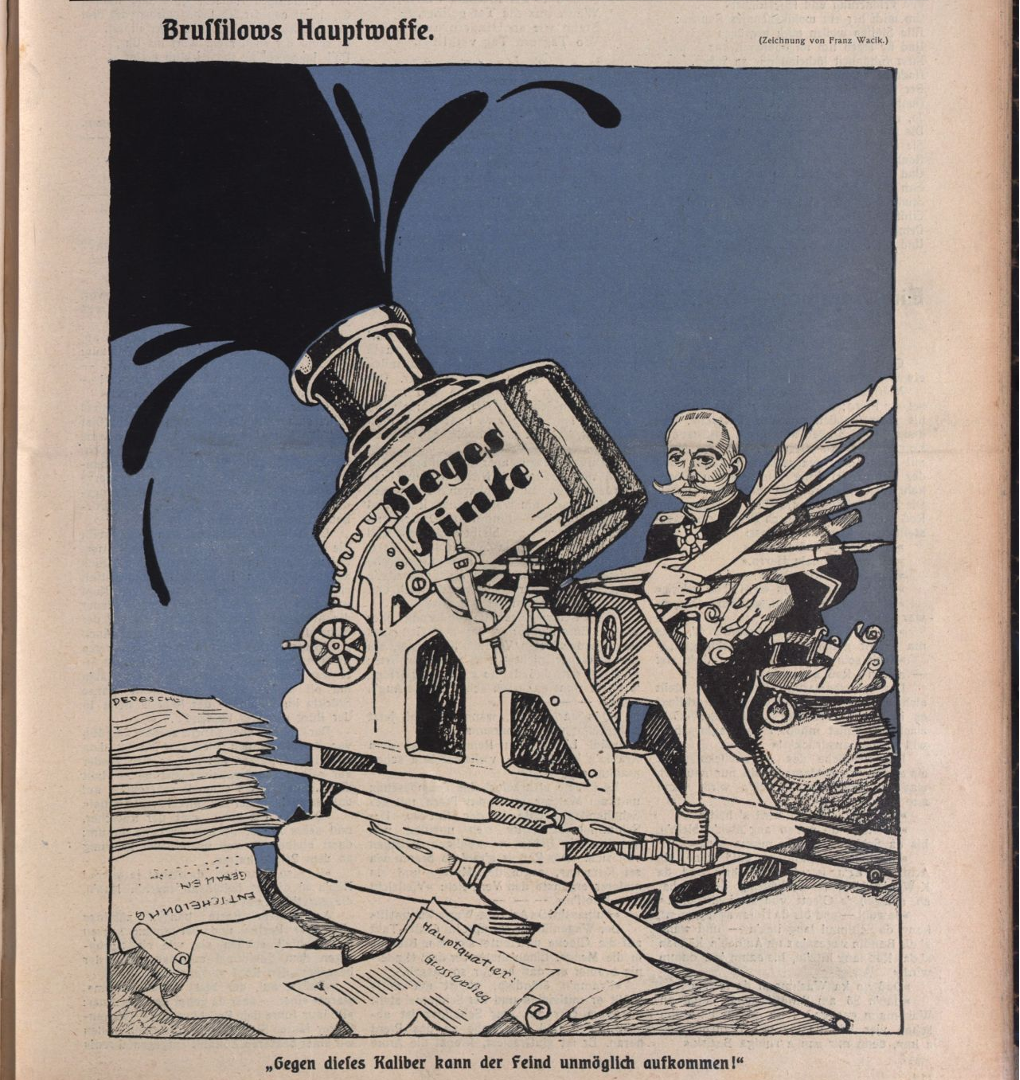

Image: "Brusilov's main weapon" (victory ink)

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:14

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:14

-

Uploaded 15/11/24, 13:03

-

Assigned reading:

Albert Fonó, "The proletarian dictatorship and the engineers," Magyar Mérnök- és Épitész-Egylet Közlönye 53 no. 13 (1919): 97. [original Hungarian here]

Albert Fonó, "The proletarian dictatorship and the engineers," Magyar Mérnök- és Épitész-Egylet Közlönye 53 no. 13 (1919): 97. [original Hungarian here]Jeffrey Herf, "Engineers as ideologues," Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich (1984), 152-188. [on campus access only]

Harley Balzer, "Soviet engineers: The rise and decline of a social myth," in Loren R. Graham, ed., Science and the Soviet Social Order (1990), 141-167. [NB: it's only the first ten pages that immediately concern us, so you can skip lightly over the remainder, but do take note of the conclusion.]

Further reading:

Evgenii Paton, "Stormy days," Vospominaniia (1958).

Kendall E. Bailes, “The politics of technology: Stalin and technocratic thinking among Soviet engineers,” American Historical Review 79 (1974): 445–469.

-

Due: Monday, 25 November 2024, 5:59 PM

In anticipation of your research paper please prepare an annotated bibliography of ten sources; at least two must be primary sources. For present purposes "annotated" means one sentence explaining the potential relevance of the source to your anticipated argument in the paper.

-

Presentation: Lukas

Assigned reading:

Oswald Spengler, "Introduction," The Decline of the West (1918) (abridged)

Choose ONE response reading according to language preference. (NB: Bazarov is the default English-language option.)

V. Bazarov, “O. Spengler and his critics,” Krasnaia nov’ no. 2 (1922), 211-231. (Original Russian text here.)

V. Bazarov, “O. Spengler and his critics,” Krasnaia nov’ no. 2 (1922), 211-231. (Original Russian text here.)Hornyánszky Gyula, review of Spengler, Társadalomtudomány 1 (1921): 230-241.

Pauler Ákos, "Uj kultúrfilozófia," Athenaeum 6 (1920): 82-87. [or PDF below]

Florian Znaniecki, Upadek cywilizacji zachodniej. Szkic z pogranicza filozofji kultury i socjologji (1921).

A. Leitis, "Реакційна література на Заході," Всесвіт no. 15 (1925): 14-15. [at libraria.ua]

A. Vul'fius, "Osval'd Shpengler kak istorik," Annaly: Zhurnal vseobshchei istorii 2 (1922), 17-30.

Jos. Šusta, review of Spengler, Český Časopis Historický 27 (1921): 175-197.

Wilhelm Bauer, "Der zweite Band Spengler," Neues Wiener Tagblatt (31 July 1922), 3-4.

Ernst Troeltsch, review of Spengler, Historische Zeitschrift 120 (1919): 281-291.

Otto Stoeffl, "Weltgeschichte als Urphänomen," Pester Lloyd (28 December 1918), 2-3.

Otto Neurath, "Anti-Spengler," in Empiricism and Sociology (1973 [1921], 158-213.

Paul Riebesell, "Die Mathematik und die Naturwissenschaften in Spenglers 'Untergang des Abendlandes'," Die Naturwissenschaften 26 (1920): 507-509.

P. Preobrazhenskii, "Освальд Шпенглер и крушение истины," Печать и революция no. 1 (1922), 58-65.

I. I. Lapshin, "Umiranje umetnosti," Ljubljanski zvon 49 (1929): 530-537. [Sorry, a translation was the best I could manage]

Image: Vladimir Mayakovsky: "All Spenglers are just Stinnes brains" [click to enlarge]

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:14

-

Presentation: Anil

Assigned reading:

Alfred Weber, "The predicament of intellectual workers"

Rudolf Kayser, "Americanism"

Stefan Zweig, "The monotonization of the world"

(All from The Weimar Republic Sourcebook)

[Karel Čapek], "We alarm and amuse M. Capek," The New York Times (May 16, 1926)

Ignotus [Hugó Veigelsberg], “America and culture,” Nyugat no. 13 (1927) [Hungarian source]

Polish option: Roman Dyboski, "Ameryka a Europa," Przegląd Polityczny T. 11, z. 6 (1929): 177-189.

Ukrainian option: V. Iurynets, "Notatky mandrivnyka," Krytyka no. 7 (1928): 18-. (go to relevant passage on page 30) libraria.ua

[click to enlarge][with subscription]

-

Presentation: Osman

Assigned reading:

"Geography at the Congress of Paris, 1919," The Geographical Journal 55 (1920): 309-312.

Maciej Górny, "Space (geography)," in Science Embattled: Eastern European Intellectuals and the Great War (2019), 119-162.

Suggested reading:

Eugeniusz Romer, Geograficzno-statystyczny atlas Polski = Geographisch-statistischer Atlas von Polen = Atlas de la Pologne (Geographie et Statistique) (1916).

Stepan Rudnytskyi, "Ethnographic boundaries of Ukraine," in Ukraine: The Land and its People: An Introduction to its Geography (1918): 118-147.

Stepan Rudnytskyi, "[Outline of the geography of Ukraine]," in Украинский народ в ее прошлом и настоящем, vol. 2 (1916): 361-380.

Rudnytskyi, "Завдання географичної науки на українських землях," Червоний шлях no. 3 (1927): 102-112. [at libraria.ua]

Anton Kotenko, The Ukrainian Project in Search of National Space, 1861-1914, PhD dissertation, CEU (2014).

Steven Seegel, Mapping Europe's Borderlands: Russian Cartography in the Age of Empire (2012). [912.0947 SEE]

Steven Seegel, Ukraine under Western Eyes: The Bohdan and Neonila Krawciw Ucrainica Map Collection (2011). [912.0947 SEE]

Guntram Henrik Herb, Under the Map of Germany: Nationalism and Propaganda 1918-1945 (1997).

Jason D. Hansen, Mapping the Germans: Statistical Science, Cartography, and the Visualization of the German Nation, 1848-1914 (2015). [912.0943 HAN]

David Gugerli and Daniel Speich, Topografien der Nation: Politik, kartografische Ordnung und Landschaft im 19. Jahrhundert (2002). [912.09494 GUG]

[click on image to see larger version]

-

Uploaded 15/07/24, 15:14

-

-

Presentation: Marina

Assigned reading:

Otto Neurath, "Through war economy to economy in kind" (1919), from Empiricism and Sociology.

Otto Neurath, "Through war economy to economy in kind" (1919), from Empiricism and Sociology.Ludwig von Mises, "War and the economy," from Nation, State, and Economy: Contributions to the Politics and History of our Time.

Hungarian alternative: Bud János, review of Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, Közgazdasági szemle (1920): 118-123.

Further reading:

"John Maynard Keynes," Pester Lloyd, 30 March 1920.

N. Liubimov, Мировая война и ее влияние на государственное хозяйство Запада: критич. изложение работы Кейнса "Экономические последствия мира" (1921).

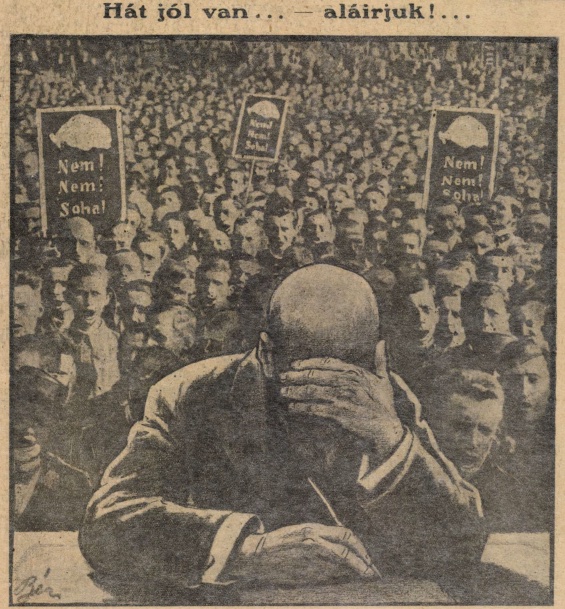

"Károlyi denunciál," Budapesti Hírlap, 3 October 1922.

"Károly Mihály cikke Keynes lapjában," Bécsi Magyar Ujság, 4 October 1922.

Jan Dmochowski, Nowe teorje monetarne (1927).

Patrick O. Cohrs, "No prospects for a lasting peace?" in The New Atlantic Order (2022), 299-348.

Adam Tooze, The Deluge: The Great War and the Remaking of the Global Order, 1916-1931 (2014).

-

Presentation: Anton

Assigned reading:

Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front (1929), excerpt.

Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front (1929), excerpt.Aladár Komlós, “Remarque’s novel All Quiet on the Western Front,” Nyugat no. 10 (1929). [Original Hungarian]

Karen Petrone, The Great War in Russian Memory (2011), 8-15, 224-235.

Czech alternative to Komlós: Otto Rádl, "Půl milionú výtisků," Přitomnost 6 no. 17 (1929): 261-264.

Russian alternative to Komlós: review of Remarque, Oktiabr' no. 11 (1929): 190-192.

Ukrainian alternative to Komlós : E. R., review of Remarque, Червоний шлях no. 1 (1930): 210-212. [libraria.ua]

Polish alternative to Komlós : (b), review of Remarque, Nowy Dziennik no. 78 (1929): 4.

Austrian alternative to Komlós: Erwin H. Rainalter, "Erich Maria Remarque und sein Buch," Radio Wien (1929): 478-479.

Slovenian alternative to Komlós: "Zakonski roman pisatelja-milijonara," Ponedeljek (17 February 1930), 4.

Further reading:

Peter Gatrell, "Russia's First World War: Remember, forgetting, remembering," in Extending the Borders of Russian History: Essays in Honor of Alfred J. Rieber (2002), 285-298.

Peter Gatrell, Russia's First World War: A Social and Economic History (2005). [940.3/47 GAT]

Vera Tolz, "Modern Russian memory of the Great War, 1914-20," in Lohr et al., eds., The Empire and National at War (2014), 257-285. [940.3/47 LOH]

Image: "Excursion on the Marne," Chudak (1929).

-

Uploaded 11/12/24, 14:45