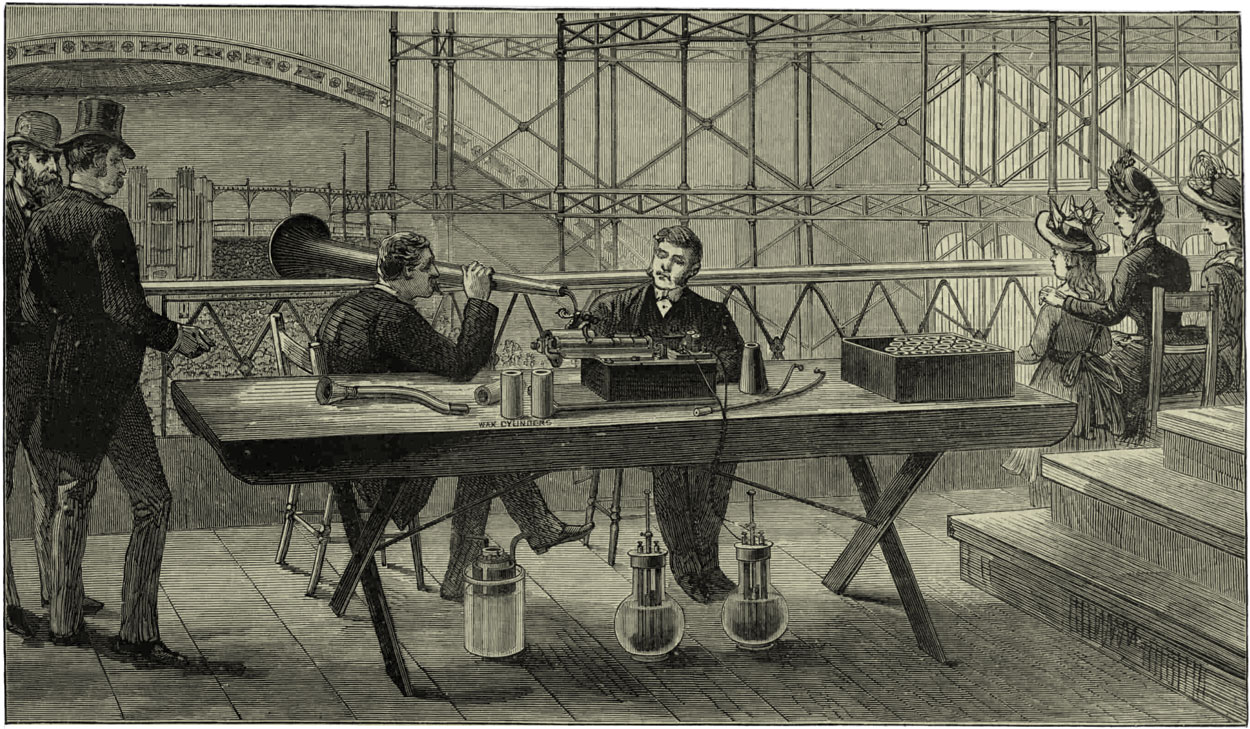

[7] November 7 — Recording culture: Comparative musicology and the phonograph

Section outline

-

Assigned reading:

Julia Kursell, "A gray box: The phonograph in laboratory experiments and fieldwork, 1900-1920," The Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies (2012), 176-197.

Aural diversion:

A student of Franz Brentano, Carl Stumpf saw psychology as the starting point for the other philosophical disciplines. He wrote The Psychology of Musical Sounds (1883) after taking a professorship in Prague, because (as he wrote in his autobiography) "the strange romantic city on the Moldau appealed to my innate wanderlust." Stumpf went considerably beyond Helmholtz in his research on the psychological perception of musical aesthetics. One phenomenon he commented upon was the discrepancy between the objective possibility of extending pitches infinitely in both directions (high frequencies and low frequencies), but the finite range of human audible resolution. We can imagine these higher notes, though we cannot hear them, but what is the psychological relation between the two? We assume that if our physiological aural range could be extended, each new note would fall naturally within our representation system and would somehow be a "natural" extension of it. But, asked Stumpf, "Is there any characteristic of notes as we hear them that justifies this supposition? Can we not equally well imagine that a prolongation of the note-series might eventually prove to be circular in character, and that as a pitch grew higher we might find ourselves back in the familiar tonal sphere, like the traveller who travels westward in what he supposes to be a straight line, though he is in fact describing a circle? It is clear that we are being led in the tonal sphere to confront a question analogous to that which has often been asked in relation to space: is space (in Riemann's definition) truly infinite or is it merely unlimited, like a circle or a ball? Here we are considering this question only from the psychological point of view." The nature of Stumpf's question can be grasped by considering a curious phenomenon: If different octaves sound "equivalent," then we may separate the phenomenon of pitch into two parts, chroma and tone-height. Chroma, or color, tells us where a pitch stands in relation to others within a given octave, while tone-height tells us which octave the pitch belongs to. Most pitches generated by musical instruments are not single pure frequencies, but a superposition of frequencies, all of which are multiples ("harmonics") of one fundamental frequency. It is actually possible to use cleverly varying combinations of harmonics to create the audible impression of changing (upward) chroma, but without changing tone-height and passing beyond the audible range. This sequence is known as a Shepard scale (courtesy of Audiolabs Erlangen):

(Here is a mathematical visualization of the effect.)

Further reading:

Julia Kursell, “Listening to More Than Sounds: Carl Stumpf and the Experimental Recordings of the Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv,” Technology and Culture 60 (2019): S39–63.

Susan Schmidt Horning, Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Studio Recording from Edison to the LP (2013).

Carl Stumpf on the Berlin phonogram archive (1908). [in German]

Robert Gelatt, The Fabulous Phonograph, 3rd ed. (1977).

Alexander Rehding, "Wax cylinder revolutions," The Musical Quarterly 88 (2005): 123-160.

Listen to an early-twentieth-century recording of Otto Abraham testing vocal tuning abilities using a Wagner motif. (From the Sound and Science database)

-

Uploaded 8/05/25, 17:07

-

Uploaded 31/10/25, 15:54

-