UGST4077 - Cultures of Quantification (Winter 2025)

Section outline

-

-

Instructor: Karl Hall

Credits: 2

Course level: UGST

Time: Mondays 15:20-16:20 and Wednesdays 9:30-10:30

Place: Monday: D105 and Wednesday: D106

Instructor's office hours: Mondays 14:00-15:00, Wednesdays 11:00-12:00, Thursdays 15:30-16:30; and by appointment

"In an inquiry concerning the improvement of society," wrote Thomas Malthus in his much-expanded Essay on the Principle of Population, "the mode of conducting the subject which naturally presents itself, is, 1. To investigate the causes that have hitherto impeded the progress of mankind towards happiness; and, 2. To examine the probability of the total or partial removal of these causes in future." The key term here is not "happiness," but "probability," for to understand the legacy of Malthus and other major figures in the rise of the social sciences, we need to look at the myriad ways that counting, measuring, and calculating became central to academic scholarship as a public good in the nineteenth century. Our historical tasks are intellectual and cultural more than technical, yet we cannot properly appreciate the present role of the quantitative social sciences without investigating how statistics, mensuration, regulation, and accounting acquired their status against a broader background of contested scientific rationalism and uneven technological development.

This is not a historical tour of the social sciences so much as it is an investigation of how the many modes of counting have been elevated to scholarly virtues and state-driven practices, as well as how historical contexts have shaped the scope and claims of the social sciences. This will be a Eurocentric course, but not one whose center of gravity lies somewhere in the English Channel. We will try to strike a balance between an introduction to comparatively canonical Anglophone topics and the exploration of broader connections throughout Central and Eastern Europe. Once the regional language skills of the students enrolled have been established, we will attempt to adjust the readings and discussions to better reflect regional concerns.

Assessment

Spontaneous 10-minute quizzes (two): 5% + 5% (This is a low-key exercise that is solely intended to motivate accountability with the readings. It will consist of several brief responses to questions raised in recent sessions.)

Midterm exam (in class): 25%

Presentation: 15% (Developed in consultation with the instructor, this will give students a chance to tie one of the course topics more closely to their own research interests. In-class time: 15 minutes.)

Participation: 15% (Warm bodies who stay awake in class.)

Review essay (2000-2500 words): 35% (The topic may, but need not, grow out of the presentation exercise. Based on modest additional reading of secondary literature, students will survey a related topic and write a synthetic historiographical essay.) Due date: April 8.

-

Arne Hessenbruch, "Bottlenecks: 18th century science and the nation state," in Mendoza et al., eds., The Spread of the Scientific Revolution in the European Periphery, Latin America and East Asia (2000), 11-31.

Further resources:

Making Europe: Technology and Transformations, 1850-2000, 6 vols. (2014-2019). [CEU Library]

Kiran Klaus Patel and Johan Schot, “Twisted Paths to European Integration: Comparing Agriculture and Transport Policies in a Transnational Perspective,” Contemporary European History 20 (2011): 383–403.Karl Hall, "Europe and Russia," in Heilbron, ed., The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science (2003), 279-282.-

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

-

[Week 2] January 15 + 20 - "The slogan of the day is uniformity": The rise, fall, and rise of the metric system in revolutionary France (and elsewhere)

Ken Alder, "A revolution to measure: The political economy of the metric system in France," in M. Norton Wise, ed., The Values of Precision (1995), 39-71.

Additional resources:

Ken Alder, Engineering the Revolution: Arms and Enlightenment in France, 1763-1815 (1997).

Henry Hennessy, On a Uniform System of Weights, Measures, and Coins for All Nations (1858), 3–30.

Simon Schaffer, “Metrology, metrication, and Victorian values,” in Victorian Science in Context, ed. Bernard Lightman (1997), 438–474.

Witold Kula, Measures and Men (1986).

Martin H. Geyer, "One language for the world: The metric system, international coinage, gold standard, and the rise of internationalism, 1850-1900," in Geyer and Paulmann, eds., The Mechanics of Internationalism: Culture, Society, and Politics from the 1840s to the First World War (2001).

O. D. Khvolson, Metricheskaia sistema mer i vesov i ee znachenie dlia Rossii (1896).-

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

-

Review of Thomas Malthus, "An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it affects the future Improvement of Society," The Monthly Review (September 1798): 1-9. [First edition OCR text] [Later editions in French, German, Hungarian, Polish, Russian, Italian] [a Czech summary]

Mary Poovey, "Thomas Malthus and the revaluation of numerical representation," in A History of the Modern Fact: Problems of Knowledge in the Sciences of Wealth and Society (1998), 278-295.

-

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

-

(Monday) Thomas Carlyle, “Signs of the times,” Edinburgh Review 49 no. 98 (June 1829): 439–459.

(Monday) Marx and Engels, "He becomes an appendage of the machine," in section 1, "Bourgeois and proletarians," from The Communist Manifesto (1848). [Read this whole section, but concentrate on the middle portion, where they spell out their position on machinery.] [Feel free to read this in any one of eighty languages.] [If you prefer, you may read the earliest English translation in The Red Republican (November 1850): 161–190 (passim).]

(Wednesday) Friedrich List, "The theory of productive forces and the theory of values," National System of Political Economy (1856 [1841]), 208-228. [original German text] [Hungarian, Russian, French]

Further resources:

M. Norton Wise and Crosbie Smith, "Work and waste: Political economy and natural philosophy in nineteenth century Britain," History of Science 27 (1989) (part 1 and part 2) and 28 (1990) (part 3).

Philip Mirowski, More Heat Than Light: Economics as Social Physics, Physics as Nature's Economics (1989).

Donald Mackenzie, "Marx and the Machine," Technology and Culture 25 (1984): 473-502.

Bruce Bimber, "Karl Marx and the three faces of technological determinism," Social Studies of Science 20 (1990): 333-351.

-

Charles Babbage, “On the advantage of a Collection of Numbers, to be entitled the Constants of Nature and of Art," Edinburgh Journal of Science n.s. 6 (1832): 334-340.

Ian Hacking, "The granary of science," The Taming of Chance (1990), 55-63.

-

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

-

Wednesday: Presentation by Mykhaylo

Assigned reading:

[John Herschel], "Quetelet on probabilities," The Edinburgh Review 92 (1850): 1-8. (The introductory pages from a much longer review essay)

Michael Donnelly, "From political arithmetic to social statistics: How some nineteenth-century roots of the social sciences were implanted," in Johan Heilbron et al., eds., The Rise of the Social Sciences and the Formation of Modernity (1998), 225-239.

-

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

-

The midterm exam will take place in class, consisting of around ten short-answer questions, and one longer essay. Many prompts will be provided beforehand to clarify expectations.

-

In class we will address the connection between discourses of objectivity in public affairs and the rise of eugenic thought.

Assigned reading:

Francis Galton, “Generic images,” Nineteenth Century 6 (1879): 157–169.

-

Presentation: Mariia

Presentation: MariiaHow historians learned to love numbers.

Discussion leaders: Pavel & Leon

Assigned reading:

Henry Thomas Buckle, "General introduction," History of Civilization in England, vol. 1, 3rd ed. (1861), 1-18. [Czech translation (PDF)] [German translation] [Hungarian translation (PDF)] [Russian translation] [Polish translation] [French translation] [Italian translation] [There is a 1919 abridged Ukrainian translation]

-

Presentations: Liza and Rebecca (Wednesday)

Presentations: Liza and Rebecca (Wednesday)Discussion leaders: Maria and Alnura and Mihaly

Assigned reading:

Michael Friendly and Howard Wainer, "The golden age of statistical graphics," in A History of Data Visualization (2021).

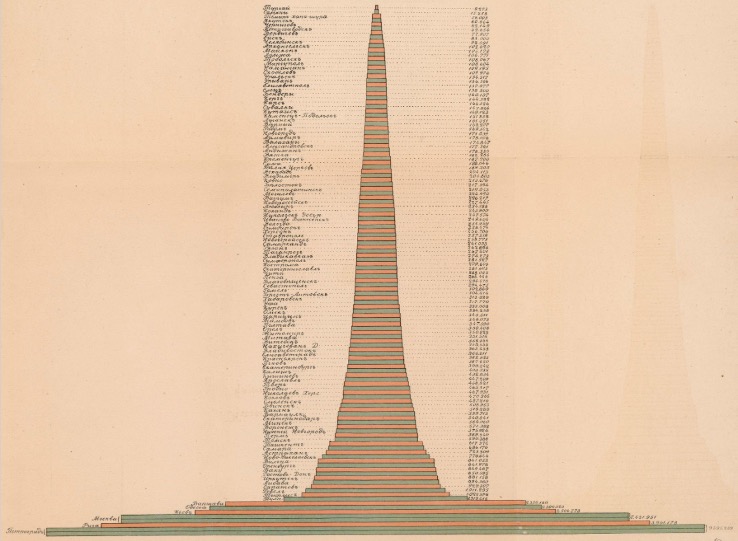

In class: some contemporary Central and East European examples...

Additional resources:

"Joint committee on standards for graphic presentation," Publications of the American Statistical Association 14 (1915): 790-797.

Willard C. Brinton, Graphical Methods for Presenting Facts (1919).

H. Gray Funkhouser, "Historical development of the graphical representation of statistical data," Osiris 3 (1937): 269-404. [JSTOR]

Histories of Data and the Database, special issue of Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 48 no. 5 (2018). [JSTOR]

See the University of Oregon's site on The Time Charts of Joseph Priestley.

-

The Golden Age of statistical graphics

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

-

Discussion leaders: Mykhaylo and Liza

Discussion leaders: Mykhaylo and LizaPresentations: Dario and Pavel

Assigned reading:

Werner von Siemens, Personal Recollections (1893), 234–243, 352–360.

Wolfgang Schivelbusch, “Railroad space and railroad time,” The Railway Journey,

41–50.-

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

-

Discussion leaders: Rita and Dario

Presentations: Thint and Alnura

Assigned reading:

Josefa Ioteyko, The Science of Labour and Its Organization (1919), 1-5.

Anson Rabinbach, The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity (1990), chapter 5.

Further resources:

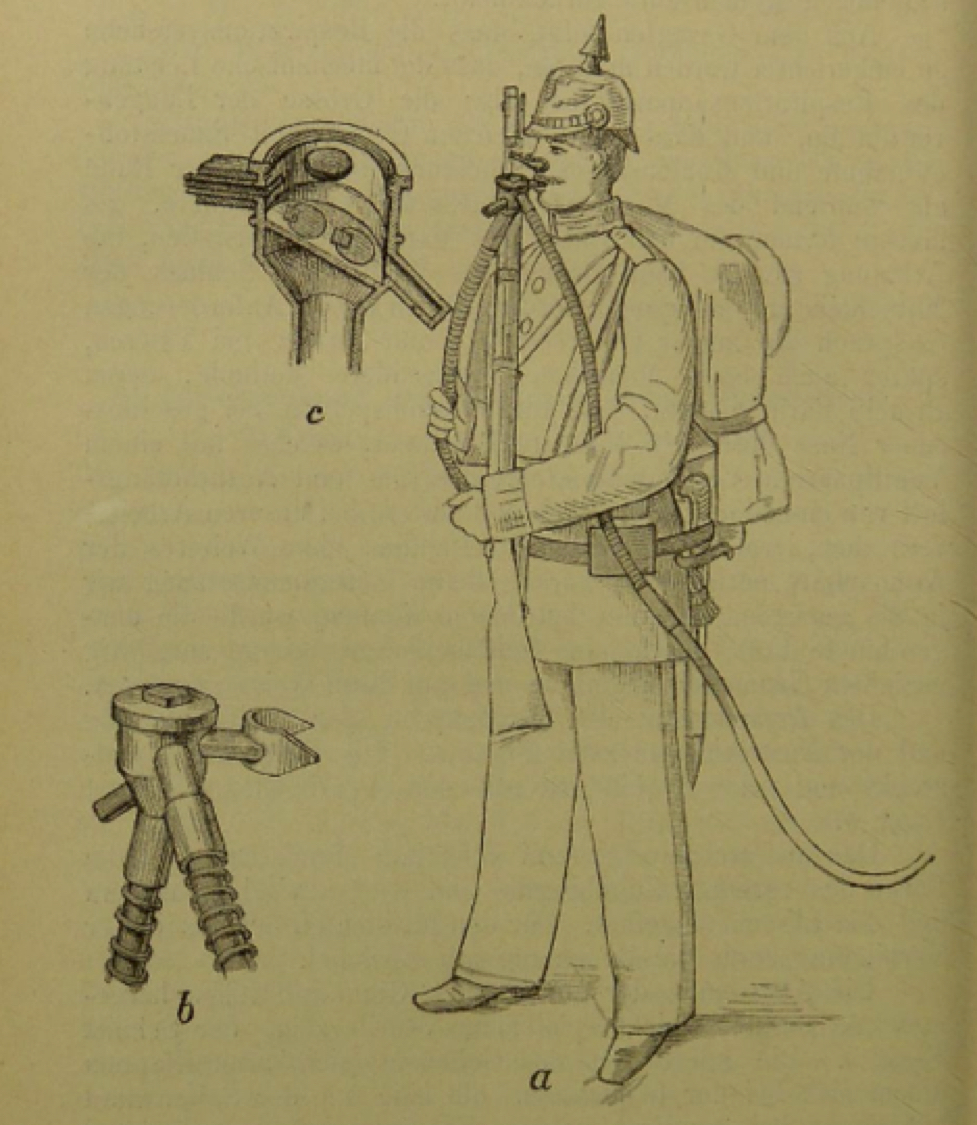

Nathan Zuntz and Wilhelm Schumburg, Studien zu einer Physiologie des Marsches (1901).

Jennifer Karns Alexander, The Mantra of Efficiency: From Waterwheel to Social Control (2008).

-

Uploaded 29/05/24, 12:34

-

-

Presentations: Mihaly and Leon

Presentations: Mihaly and LeonDiscussion leaders: Dario and Thint

In the final week of the course we will investigate one of the most important tools of the modern state: the census. The instructor is still developing resources for this section, but our aim will be to draw upon the language skills of the actual student cohort in order to make a series of comparisons in the classroom about how social class, native language, religion, and profession of citizens and subjects were collated (often imperfectly) by the state. Whether it be the census of the Russian Empire in 1897, or that of the British Empire in 1901, or the Habsburg Austrian census of 1910 and its Hungarian counterpart, or the 1890 American census (famous for employing tabulating machines to process the data), or the German census of 1895, or the French census of 1881, or the 1891 Norwegian male census, or the 1861 Italian census, or the 1888 Swiss census, or the 1881-1882 Ottoman census, we want to study the relation between new forms of technical facility and knowledge of populations.

Assigned reading: Christine von Oertzen, "Machineries of data power: Manual versus mechanical census compilation in nineteenth-century Europe," Osiris 32 (2017): 129-150.